Editing and modelling the〈foreign/〉: the languages of the Histoire ancienne

Miniature from Dijon, BM, MS 562, fº 9r

My post today is about the languages of the Histoire ancienne jusqu’à César (HA). To say that the HA is written in French is both obvious and misleading since it masks a plural reality. Different linguistic competences and textual cultures are visible while reading the manuscripts of the HA. This variety is sometimes barely perceptible; at other times it is apparent. A simple example is maybe enough to explain what I mean. Scribes such as the one responsible for the codex Paris, Bnf, MS f. fr. 20125 do not always ‘Gallicize’ proper names. In the Roman sections of the story, for instance, proper names are given Latin morphemes: ‘Africam’ (Latin accusative placed with transitive French verb), ‘Turne’ (Latin vocative surfacing in an exordial position of a new discursive string), and so on. Where do these forms situate themselves? Somewhere on an imaginary continuum between Latin and French, are we already on the side of French or are we still on the side of Latin? Is a Latin inflection an attempt to ‘save’ the Latin through a morpho-syntactic ‘relic’ left floating on the textual surface? Or is Latin morpho-syntax a way to give the French the solemnity of a Latinizing ‘diction’? The plural in the title of this post (languages) is based on one of the features of the HA that attracted our attention from the outset: languages as referential objects, or languages that speak about themselves. In its numerous irruptions in the narrative, the voice that tells the story is often sensitive to linguistic diversity. In the following Biblical passage, the Geon river (Gn 2:13) is glossed ‘Nile’ en nos plus usé language (in our common/ordinary language) (§02_28), a phrase employed in opposition to the language of the escriture (the Scriptures):

- Lun de ces fluns apele· Gyon lescriture· [et] nos le clamons le nil en nos plus use language· [Scripture calls one of these rivers Geon, while we call it the Nile in our most common (literally ‘used’) language]

Interesting references to language are recurrent in the HA. In the following instance, the narratorial voice ‘speaks’ to its audience, addressing one of the issues that most excited medieval curiosity: namely, who spoke first and in what language (§02_13-14):

- E quel lenguage parla adans· uoles uos que ie uos die: Tuit soiez certain quil parla p[re]miers e tote sa uie en ebriu language· [And which was the language Adam spoke? Do you wish me to tell you? You must all know that he first spoke Hebrew and did so his entire life]

Our project team wanted to capture and give to these data an intelligible and exploitable shape. We decided to record this metalinguistic information through a series of xml-TEI (=Textual Econding Initiative) ‘elements’, complemented by ‘attributes’ meant to clarify their type or ‘meaning’. We have an element for quotations (e.g. in Scriptural Latin): 〈q〉; an element for references to languages: 〈rs〉 (= ‘referencing string’); and an element for words or phrases ‘belonging to some language other than that of the surrounding text’: 〈foreign〉. foreign The following instances of our xml markup will provide you with an idea of how we’re using it and of how coding is a form of interpretation (§702_07 = Anne Rochebouet’s 2015 edition, 3.54):

- La feme le uit bel si lencheri mout [et] le nori ausi tres doucement que ce se fust de sa porteure· [et] si le noma [et] apela: sparticum en 〈rs type="metaling"〉persant language〈/rs〉qui uaut autant [et] sone com 〈foreign xml:lang="lat"〉quaiaus〈/foreign〉 en 〈rs type="metaling"〉langue latine〈/rs〉·

[The woman saw in him a beautiful child, so that she cherished him dearly, and brought him up as tenderly as if he were her own son. She called him Sparticum in Persian, which means and sounds like 'little dog' in the Latin language]

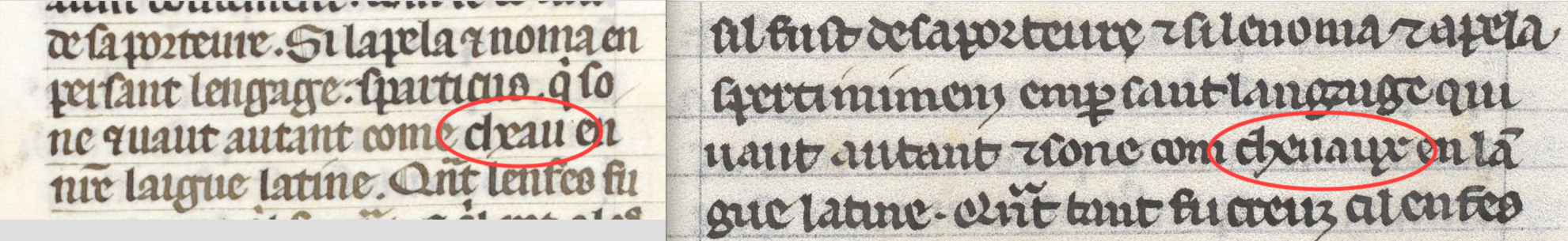

This passage is taken from the youth of Cyrus, king of the Persians, who, in Justinus’ account (I 4, 10-14) of the king’s legendary birth, as a child was named Spargos ‘for so the Persians call a dog’ (‘quia Persae sic uocant’). Spargos becomes Sparticum; canem is translated as quaiaus (little dog); and the generic statement about what the Persians call a dog, becomes a gloss both about the signified (uaut = French vaut ‹- valoir ‘to be worth, to mean’) and the signifier (sone ‹- soner ‘to sound’). If this is the case, then in what language is the signifier quaiaus? Not being Latin, the natural answer should be French. The answer is correct, but partial. The variant reading cheuaux (Fr. ‘cheval’, horse), which we have in other manuscripts (e.g. in the manuscripts of the 13th-c. abridged version: e.g. London, BL, MS Additional 19669, fº 123rb; The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, 78 D 47, 99ra) suggests that quaiaus was not always understood. This morphing of a puppy into a horse may have a paleographic explanation: forms of cheau (alternative form for for quaiaus, ‘little dog’, in the Acre manuscripts—cf. London, BL, MS Additional 15268, fº 174va) and cheuaux (for standard cheval) could look very similar.

Details from London, BL, MS Additional 15268, fº 174va (cheau), and London, BL, MS Additional 19669, fº 123rb (cheuaux)

With its ‘conservative’ script [k] + a as opposed to the palatal [ʃ] + e, forms like quaiaus (instead cheaus ‹ catellus) are recurrent in texts copied in the North-East of the French domain. What is this scribe doing by ‘saying’ in a certain variety of French that in ‘Latin’ Sparticus, the Persian name for Cyrus, means and sounds quaiaus? On the one hand, we know that old French latin could stand for a variety of things: apart from Latin, it may stand for the language of high culture, or simply for any sort of intelligible language, including the vernacular, as the passage above may imply. On the other hand, en langue latine could truly mean ‘in Latin’: i.e. a paraphrase of Justinus whereby Persian sparticum (Spargos) means and sounds in Latin as quaiaus (almost) means and sounds in the vernacular: i.e. puppy.

Coming back to our encoding: what are we learning from our practice? What are the languages that are mentioned in the HA? In transcribing Paris, BnF, f. fr. 20125, we’ve encoded 104 metalinguistic instances. On the basis of our markup, the French language is never mentioned as such: it’s designated simply as our language. Instead, the languages of the others, the foreign languages, are given a label. For example, the Parthians that killed Crassus speak ‘arabois la[n]guage’ (Arabic) (§1237_09). In Hellenistic Egypt, Ptolemy II Philadelphus is said to have had the Hebrew Law (the Old Testament) translated into his ‘grijois language’ (§1091_04)—a reference to the legend of the Septuagint Greek translation of the Old Testament. As we’ve seen, Latin is usually called Latin, though Scipio the African spoke to Hannibal in ‘romain language’ (§996_01). On the other hand, the Punic or African language spoken by Hannibal is called ‘lubien language’ (Libyan language) (§994_02), and so forth. We also have a mention of the Indian language in opposition to Alexander the Great’s Greek language (§832_02 - 03) no doubt to enhance its exotism. Finally, language occurs in ‘mimetic’ contexts. In his travels to India, when Alexander meets a ‘prestre’, the latter greets the former ‘en son langage’ (in his language) ‘selonc la costume’ (according to their habits).

From Chris Pack Blog Post

One of the virtues of our edition is not yet fully apparent. The xml encoding that we’re applying over the late 13th and 14th-c. written code of the manuscripts is not visible on the public interface at the moment. However, it has been used in the background for a variety of queries and operations on the text. It’s a research framework which Paul Caton, Geoffroy Noël and Ginestra Ferraro at KDL have created to model the textual components and metadata of the edition and their relations. This is giving us the possibility to have access to, to search, to reflect upon and then use the data in a variety of ways to come up with further ideas, interpretations, and so forth. But what we do with our encoding is of course only half the story. The xml language we use to encode our texts is flexible: it can be used to respond to our research questions but also to those of other scholars. By doing what we’re doing, we are not just dealing with what the HA has to say about x or y; we’re also trying to shape our data in order to allow other researchers to use/transform/adapt our data to attain their own specific research aims.

In digital humanities (DH) research connecting textual phenomena and patterns to conceptual principles is facilitated by what is called a modelling process (Chris Pak and Arianna Ciula are contributing to an ongoing research project attempting to pindown the practices of modelling in DH). The modelling of the data in TVOF (e.g. adoption of relevant parts of the TEI schema combined with a modular software development supporting operations such as annotation and querying of the data) is obviously geared towards addressing our research questions. However, by adopting DH modelling practices which are informed by and aim to support pluralistic notions of textuality that go beyond one single perspective on texts, we hope our modelling would allow other researchers to identify other interesting patterns.

Managing the large amount of data generated by editing the HA is one the challenges of TVOF project. Manuscripts, texts, traditions and languages are subject to a persistent metamorphic, stretching and twisting process; but they also show traits of inherent connectivity. Modelling is essential in the understanding of the (historical, cultural, linguistic, pragmatic…) properties of this formal and relational dynamism. Finally, modelling is a demystifying approach, since it makes explicit the bias inherent to any fixation of criteria for knowledge.

References

Ciula, Arianna (2017). ‘Digital humanities and practical memory: modelling textuality’, Estudos em Comunicação, 25,2: 7-17.

Derrida, Jacques (2012). ‘What is a “Relevant” Translation?’, in Laurence Venuti (ed.), 2012. The Translation Studies Reader. London and New York: Rutledge, 365-88 (English trans. Laurence Venuti originally appeared in Critical Enquiry, 27 (2001): 174-200)

Rochebouet, Anne (ed.) (2015). L'Histoire ancienne jusqu'à César ou Histoires pour Roger, châtelain de Lille, de Wauchier de Denain. L'histoire de la Perse, de Cyrus à Assuérus, Turnhout: Brepols (Alexander Redivivus, 8)