Before the knight fell: historicizing the art of war in the Histoire ancienne

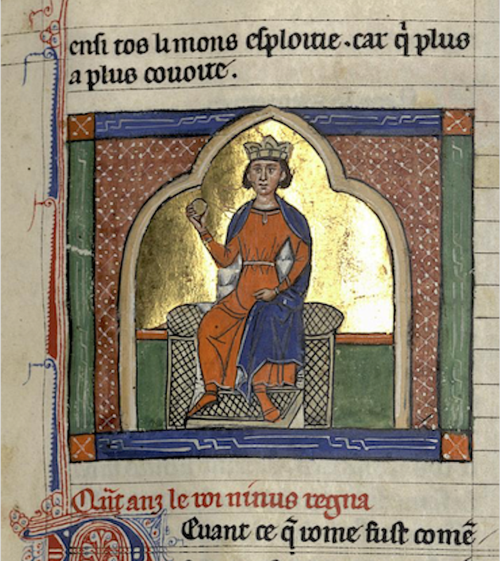

Dijon, Bibliothèque Municipale, MS 562, f. 62r. King Ninus.

The Genesis section of the Histoire ancienne is a sophisticated montage of ancient sources in which biblical history is combined with contemporary events of ancient history. It is the first French work of its kind, but it continues (and exploits) an ancient Latin tradition starting with Jerome’s Chronicon (late 4th century; a translation and update of the earlier lost Chronicon of Eusebius of Cesarea, written in Greek) and Orosius’ Historiae adversos Paganos (5th century). The author of the Histoire ancienne was standing on the shoulders of giants. Nonetheless, he produced original reflections on some controversial points and when original, his contribution sheds light on his audience's knowledge and prejudices.

This is the case with the treatment of the first Assyrian king Ninus, who holds a pivotal role in the early history of mankind according to our ancient historians. A contemporary of Abraham and the founder of Niniveh, Ninus is described by Christian sources as the initiator of profane customs: he fostered idolatry by adoring as a god his own father Belus. Prior to that, pagan sources had identified him as the initiator of wars. According to Justin (2nd century) in his epitome to Pompeius Trogus, before Ninus rulers used to protect the borders of their domains rather than extend them. This was discussed by Saint Augustine in the fourth book of his De Civitate Dei, and it was common knowledge among historians of the Middle Ages.

Ninus’ wife Semiramis is a key figure in this history. Ancient historians agree that she ruled over the Assyrians after her husband’s death and that she was a ruthless queen. Her controversial legend is retold repeatedly. While, according to Justin and Orosius, Semiramis was the founder of Babylon, Jerome says that she enlarged and fortified an existing settlement. In both cases, Babylon is considered an original possession of Ninus’ dynasty.

Edgar Degas, Semiramis Building Babylon. Copyright RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d'Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

Surprisingly, in the Histoire Ancienne we find a detailed account of how Ninus conquered Babylon with the first military campaign of world history, after which he assigned the city to his queen. The Histoire ancienne depicts vividly the preparation of the campaign and the battles. However, the most interesting aspect of the Histoire ancienne’s account is the reference to pre-chevaleresque ancient warfare. In Ninus’ time, horses and swords were not used in battle:

Li rois Ninus assambla ses amis et ses gens quanque il en pot avoir par doner o par prometre s’il iauoient mestier de s’aïe mout li vindrent bien et si home et cil de sa lignee. Quant toutes ses gens ot assamblees, il en ala sor les Babilonieins qui bien savoient sa venue. Cil de Babilonie orent lor gens quancunques il porent mises et assamblees ensamble, et vindrent contre le roi Ninum a l’entrer de lor terres, quar bien sachiez que grant et hardi et fort estoient, ne ne doutoient a morir nulle choze. Adonques en celui tens n’esteit ni aubers ni haumes, ne ne savoient de chevaus courir, de fer, beau segnor, nulle riens car n’en auoient noient veü faire. (BNF fr. 20125, par. 78, 3-4)

‘King Ninus gathered his friends and his people, those whom he managed to call by making gifts and by promising [that] if they were able to help him, many advantages would come to their men and to their descendants. When he had gathered all these peoples, he attacked the Babylonians, who were well aware that he was coming. Those of Babylon had gathered their people as best they could, and they went against king Ninus at the border of their lands, because—you should know this—they were tall and brave and strong, and they were not afraid of dying. At that time, there were no hauberks and helms, nor they were able to ride horses, or use swords—good lords—nothing [of these things] because they have not seen anything done [or made] [in such a way].’

Assyrian chariot, relief from Niniveh (about 650 BC). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

According to the author of the Histoire ancienne, Ninus’ army was composed of men using projectiles from chariots. According to medieval historians, ancient men were giants, too big to ride horses (BNF fr. 20125, par. 78,5). The technical evolution of war, the author of the Histoire ancienne says, occurred later, during the third age of the world (BNF fr. 20125, par. 79,1).

However, the differences between the military techniques of the ancient world and those familiar to the 13th-century French audience have another important consequence: the impossibility of naming any distinguished warrior:

Ne truis en l’estorie les nons de ceaus qui bien le firent, quar ni ot sor les chevaus encontre perilous, ni joste de lance de fraisne par aatine faite ne entreprise. (BNF fr. 20125, par. 79, 2)

‘I can’t find in the estoire the names of those who performed well, because there was neither dangerous clash on horses, nor was any joust made with wooden lances after provocation.’

Readers and listeners of the Histoire ancienne expected the names of Ninus’ paladins because they were members of a warrior aristocracy familiar with the chansons de geste. Individual heroism was for them the decisive moment of any battle. The author of the Histoire ancienne, who was certainly familiar with a wider range of literary works, seems to hold the same opinion. He was also a reader of classical Latin epic, where recounting a war without named heroes was unthinkable.

London, British Library, Add. MS 15268, f. 106. King Ninus. Reproduced with the permission of the British Library Board.

Later on in the Histoire ancienne, the narrator comes back again to his imperfect knowledge of Ninus’ campaign against Babylon:

Et au tans que Ninus regna tot droiturerement quant Abrahans fu nes ot duré li siecles, c’est tres Adam le premerain home, trois mil ans et·c·et·lxxx·et·iiii. Et ci en dedens ne seurent onques historiographiein conter ne parler se petit non d’estor ne de bataille que gent feissent ne comensa. Cent ains uiuoient ausi et queroient lor uiandes par bois et par silves li pluisor com se ce fussent bestes. (BNF fr. 20125, par. 371, 2)

‘At the time when Ninus reigned, exactly when Abraham was born, the world had lasted 3184 years from Adam, the first man. Historiographers are not able to recount or say much about the fights and the battles conducted and begun in this period. Most of those men lived for a hundred years, and searched for food in woods and forests as if they were animals.’

Here, we find one of the few occurrences of the word for ‘historiographer’ in Medieval French. In a paradoxical way, the author of the Histoire ancienne does not evoke the technical and erudite dimension of the transmission of knowledge about the past, as one may expect, but rather to justify his incapability of naming heroes and the dryness of his account. Moreover, if we return to Justin, Eusebius and Orosius, we realize that Ninus’ war against Babylon is not told by ancient historiographers, and is most likely an invention of a medieval writer (maybe the author of the Histoire ancienne himself). In any case, and particularly if the account of Ninus’ campaign was a recent invention, these passages of the Histoire ancienne display an interesting dialogue between sources, vernacular authors and their public on the complex background of earlier vernacular literature.