Medieval Francophonia: the Western Edge

Keith Busby is Emeritus Professor in the Department of French and Italian, University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA. His most recent book, French in Medieval Ireland, Ireland in Medieval French: The Paradox of Two Worlds, was published in 2017 by Brepols.

Much interest has been shown in recent years in language and literature in ‘Medieval Francophonia’, particularly in works composed and manuscripts copied in French in Italy, and further to the East in the Crusader states (‘Le français d’Outremer’). In this brief contribution, I will look at the other side of the map. Anglo-Norman was both a spoken and written vernacular in the centuries after 1066 in England, where the first literary texts begin to appear in the early twelfth century. The Normans quickly moved into Wales, and on May 1, 1169, a small group of mainly Welsh Normans (Cambro-Normans) led by Robert FitzStephen crossed the Irish Sea and landed in Bannow Bay, Co. Wexford, on the southeast coast of Ireland. They were the first of several contingents of French-speakers, assembled by Richard FitzGilbert de Clare, Earl of Pembroke, in response to a request by Diarmait Mac Murchada, dispossessed king of Leinster, for help in regaining his throne. Richard is better known to history as Strongbow, and shortly after his own arrival in Ireland, he married Diarmait’s daughter, Aoife, in Waterford on August 25, 1170. Support for Diarmait quickly turned into colonisation and much of Ireland was soon granted to the invaders by Henry II, the first English king to visit Ireland in 1171.

Daniel Maclise, The Marriage of Strongbow and Aoife (1854, oil on canvas). The National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin.

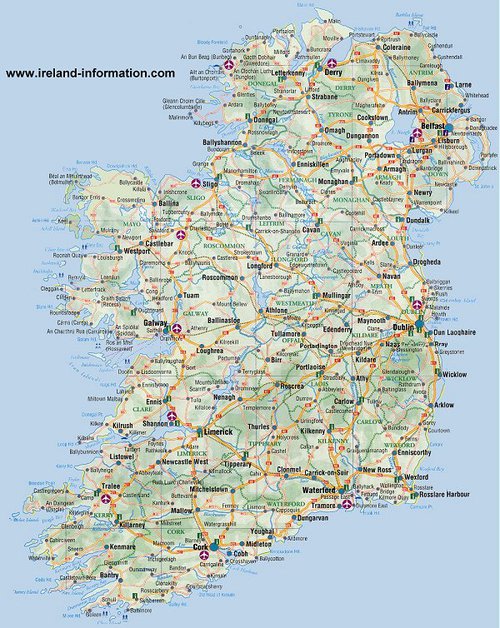

Map of Ireland.

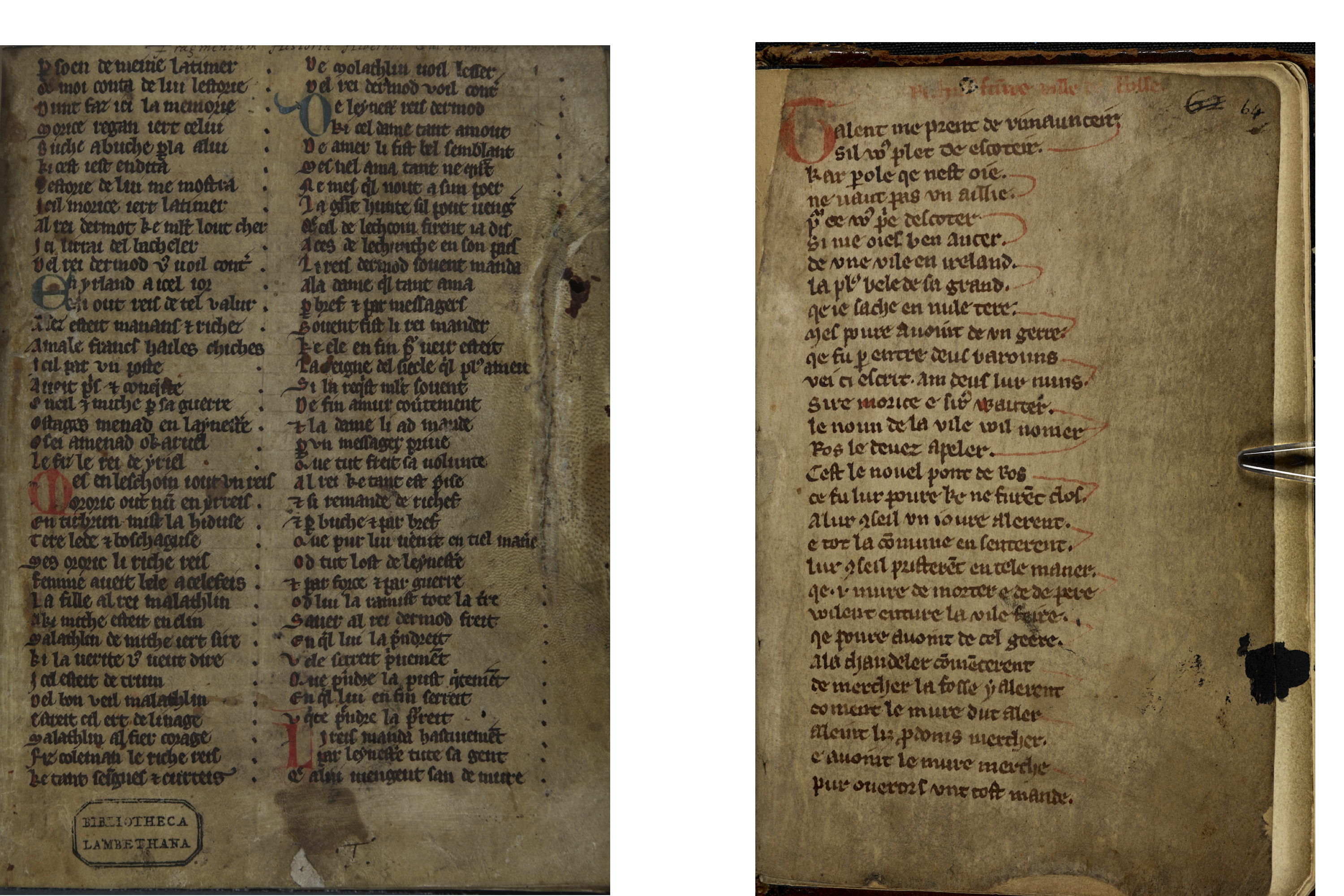

A number of literary texts were written in Hiberno-Norman French, such as the Geste des Engleis en Yrlande (c. 1190), formerly known as The Song of Dermot and the Earl, and The Walling of New Ross (1265). The first is a pseudo-chronicle in the form of a chanson de geste relating the story of the invasion and was probably written for one of the newly-established colonial households, while the second is an urban poem which celebrates the construction of defenses around the town of New Ross. Both are anchored in different ways in Old French literary traditions, belying any notion of Irish Francophonia as a cultural outlier. The new residents of Ireland had apparently brought their literary culture with them. There is evidence of French being spoken in Ireland well into the fourteenth century, for example during the trial of Alice Kyteler, accused of witchcraft in Kilkenny in 1324, and of French songs being sung on the streets of the town around the same time. French inscriptions are found on gravestones in New Ross, Kilkenny, Youghal, and elsewhere in the region between c. 1275 and c. 1325. The use of French in Irish towns declines during the second half of the fourteenth century, to be replaced by English and a resurgent Irish. French made few inroads in rural areas, although the existence of interpreters confirms that there was frequent contact between Irish and French speakers from the very beginning.

The conquest of Ireland met with some resistance from the native Irish aristocracy, but French-speaking communities were established from Dublin southwards to just north of Cork, including the towns of Waterford, New Ross (Co. Wexford), Wexford, Kilkenny, and Youghal (Co. Cork). Francophones soon moved further north and west into all parts of the island, although most surviving examples of the language are from the Southeast. French had been spoken earlier in the first Cistercian monasteries established in Ireland, starting in Mellifont, Co. Louth (1146), where many of the first brothers were either from houses in France or England where French was the principal vernacular. As in England, Scotland, and Wales, French-speakers remained a small minority of the total population throughout the Middle Ages.

Left: The Geste des Engleis en Yrlande (c. 1190) in Lambeth Palace Library, Carew 596, p.1 – reproduced with kind permission from Lambeth Palace Library.

Right: The Walling of New Ross (1265) British Library, Harley 913, f. 64r – reproduced with permission from the British Library Board.

Waterford seems to have been the centre of medieval Irish literary Francophonia. A number of manuscripts containing French, including those of the Geste and the Walling were copied there, probably in the Dominican monastery of St Saviour’s. Histories of Old French literature usually make passing mention of the work of Jofroi de Waterford, brother of St Saviour’s, whose three translations from Latin are preserved principally in Paris, BnF, fr. 1822. They are: La gerre de Troi (from the De excidio Troiae of ‘Dares Phrygius’), Le regne des Romains (from the Breviarium Historiae Romanae of Eutropius), and the Secret des secrets (from the Secretum secretorum of the Pseudo-Aristotle). The first two are relatively literal translations while the third is freely adapted by omissions and large-scale insertions, the end-product resembling a mirror for princes-cum-encyclopedia.

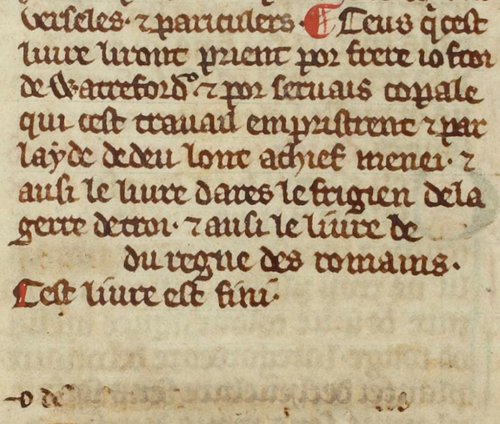

At the end of the Secret, Jofroi names his collaborator on the three texts, Servais Copale, who seems to have been his scribe; Servais had already been identified in 1946 as coming from the town of Huy, near Liège. The language of BnF, fr. 1822, is not surprisingly a strongly marked Walloon dialect with underlying Anglo- or Hiberno-Norman features, confirming both Servais’ origin and Jofroi’s insular idiom. Mention of ‘les exemplaires de Paris’ as the sources of the Secret had long led scholars to assume that Jofroi and Servais had met and worked together in Paris, but my recent identification of Servais as a customs official and merchant in Waterford locates the composition of the texts securely to the city in about 1300. ‘Les exemplaires de Paris’ most likely means ‘the copies from Paris’. Jofroi’s use of the three Latin originals and numerous other sources used in the Secret shows that he had a considerable library available to him, which may, of course, have included books acquired from Paris. The attribution of Jofroi’s works to Ireland increases many times over the corpus of Hiberno-Norman literature and is a reminder that peripheries can be culturally more central than they appear. Waterford at the turn of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries was not a backwater. It was a thriving international port with a sizeable population of foreigners, particularly from England, France, and Italy. Its various religious houses guaranteed a degree of literacy and access to books. Sister houses on the Continent could easily have been a source of books in St Saviour’s library, known to have been housed in a separate building.

At the end of the Secret, Jofroi names his collaborator Servais Copale. BnF, fr. 1822, f. 143va, detail. (Source: Gallica)

The collaboration of a francophone Irish Dominican monk and a Walloon customs officer and merchant at the beginning of the fourteenth century may look like an oddity, but we should remind ourselves that Chaucer’s father and grandfather were merchants and that the poet himself was a public servant. As well as providing a caution against imposing rigid cultural and social divisions on medieval society, medieval Irish Francophonia from the late twelfth century through the middle of the fourteenth shows us how dynamic and complex the transfer of languages and cultures can be. It is a product of colonial, cultural, monastic, and urban forces not without similarities to English Francophonia after Hastings, but its establishment on the smaller island was subject to quite specific local conditions. Just as scholars are beginning to speak of ‘Old Frenches’ to distinguish between the various idioms and dialects of the language, we might be well advised to follow the advice of a recent Italian publication entitled Francofonie medievali and speak of ‘Medieval Francophonias’ in the plural. From Ireland to Italy, and beyond to Cyprus and the Levant, the langue d’oïl had a long and varied reach.

Keith Busby

References

Keith Busby, French in Medieval Ireland, Ireland in Medieval French: The Paradox of Two Worlds (Turnhout: Brepols, 2017).

Anna Maria Babbi and Chiara Concina, ed., Francofonie medievali: Lingue e letterature gallo-romanze fuori di Francia (sec. XII-XV) (Verona: Edizioni Fiorini, 2016).