Alexander Across Religious Boundaries: A Thirteenth-Century Hebrew Translation of the Roman d'Alexandre

Caroline Gruenbaum is a PhD candidate at New York University in the department of Hebrew and Judaic Studies, and is affiliated with the Program in Medieval and Renaissance Studies. Her dissertation analyzes the function and form of Hebrew literature in medieval northern Europe, emphasizing places of literary borrowing and innovation. She holds a B.A. from Brown University in Medieval Studies, Judaic Studies, and Classics. Follow her on Twitter @cgruenbaum.

In a fragment of a thirteenth-century Hebrew translation of the Roman d’Alexandre, the author has seamlessly included into the Hebrew text a couplet in Hebraico-French, French written in Hebrew characters. This editorial decision is especially noteworthy, as the couplet is one of only a handful of lines extant in Hebraico-French, and it appears in one of only two translations of the medieval Alexander romance from French to Hebrew. Why did a Hebrew author make this surprising decision to leave the couplet untranslated?

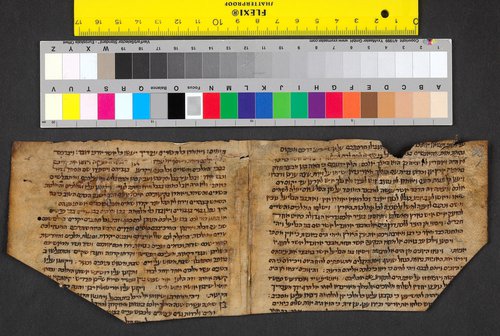

The fragment itself, Munich cod. Heb. 419XX, borrows from the Roman d’Alexandre and is part of a larger tradition of Alexander in Hebrew in the Middle Ages. The medieval Hebrew Alexander romances combine rabbinical stories about the military leader with non-Jewish stories that originate in Greek and Latin (i.e. Historia de Preliis), transmitted to Jewish communities through Arabic language versions. Although part of this relatively widely-attested Hebrew tradition of Alexander romances, Munich Heb. 419XX appears to be one of only two medieval Hebrew translations drawing on a specifically French source.

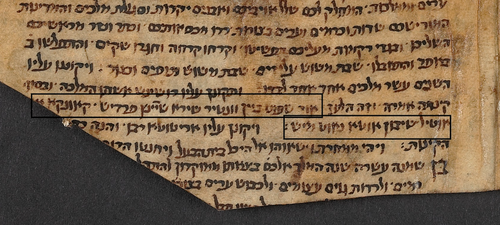

At the end of her Hebrew elegy for her husband Alexander, the widowed Roxane speaks a rhymed couplet in Old French:

אור שפוט ביין וונטיר שירא שיינץ פרדיש

קאונקא א(ן) אוטיל שיבון אוטא נאוט מיש

A thirteenth-century Hebrew fragment of the Roman d'Alexandre, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München, Cod.hebr. 419(20, image number 1

The transliteration into Old French reads:

Or se peut bien vanter, sire, sainz paradis [Now, sir, blessed Paradise can boast

Que onque e[n] autel si bon ote ne ot mis. That never on an altar was so good a sacrifice placed.]

The couplet here is highlighted. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München, Cod.hebr. 419(20, image number 1

The inclusion of transliterated French verse into a thirteenth-century Hebrew text was highly unusual. Not only are there very few examples of Hebraico-French in any medieval Jewish text, the majority of those examples are single words to assist with difficult Hebrew vocabulary, as in the commentaries of Rashi (1040-1105). The well-known medieval Jewish rabbi translated unusual Hebrew words from biblical texts into Hebraico-French to assist his readers, evincing that his community spoke French as their vernacular. While most Jewish men in medieval northern France, as well as some women, read prayers in Hebrew, they could not all read fluently in that language. By keeping the couplet in Old French, the author can be certain that men, women, and children could understand, suggesting the possibility of an oral reception.

The fragment includes a speech Alexander gave before his death, the separation of his kingdom between his five military leaders, and Roxane’s eulogy. The text refers to the statue of Alexander erected on his grave, as well as the twelve towns he founded, and culminates with the search for his two murderers, Antipater and Andoinos who are caught and tortured. This section of the Alexander narrative comes from the Mort Alixandre, the fourth branch of Alexandre de Bernay’s Roman d’Alexandre.

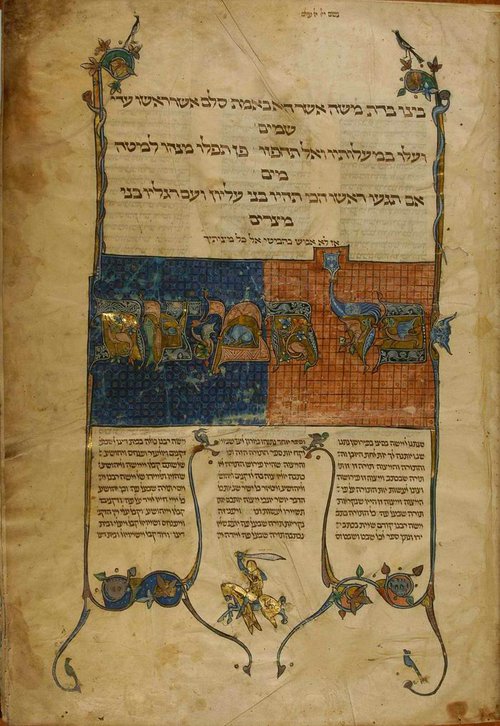

Even religious texts had knights in the margins, as in this thirteenth-century copy of Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah, a medieval compendium of religious law. The Kaufmann Mishneh Torah, Budapest, Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences / Magyar Tudományos Akadémia (MTA), Oriental Collection, MS A 77/I-IV, fol. 2a (1296, northern France) http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/en/ms77a/ms77a-002r.htm.

Reproduced with permission from the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

The couplet is not attributed to Roxane in the original but is delivered by Calaus Menalis, a royal son who leaves his home to serve Alexander. As Kirsten Fudeman suggests in chapter three of her Vernacular Voices: Language and Identity in Medieval French Jewish Communities, the Hebrew author places the couplet in Hebraico-French for Roxane to emphasize the femininity of Old French, in opposition to the masculinity of Hebrew. A vernacular, like Old French to the Jews, is often referred to as the ‘mother’ language, while the literary, text-based language of Hebrew has a masculine association, largely restricted to the learned male elite.

Since medieval French Jewish communities lacked non-religious poetry, the scribe had no recourse to put the couplet into Hebrew poetry. His decision to leave the line untranslated reflects an effort to retain the prosody and tone of the original, as well as the wordplay. In the Old French original, the line ‘Anquenuit se porra vanter sains Paradis/C’onques en son ostel tel oste ne fu mis’ (This very night blessed Paradise will be able to boast/That never before on its altar was such a sacrifice placed) plays with the double meanings of ostel as ‘lodging’ and ‘altar’, and oiste or oste as both ‘guest’ and ‘sacrifice.’ Maintaining the French words for this line preserves the emphasis of these double meanings: Alexander is a sacrifice on an altar, and a guest in his new abode in heaven.

This couplet represents a French-Jewish engagement with Old French textual sources, showing that Jews brought literature cross-culturally into the Hebrew sphere (Hebrew literature from medieval France did not have its own independent tradition of courtly love or romance). We also have medieval rabbinic writings that mention knightly tournaments, and Hebrew manuscripts beautifully illuminated with images of knights (see left).

Although stories of knights or pagan emperors like Alexander do not appear to promote Jewish ideals, medieval Jewish communities had an appreciation for tales with non-Jewish origins. From this fragment, even the pagan Alexander emerges as a hero, whose eulogy ought to be heard in a language all in the audience could understand—a universal hero whose highly-regarded status transcended religious boundaries.

Caroline Gruenbaum

Bibliography and Further Reading

Bekkum, Wout Jac van, trans. A Hebrew Alexander Romance According to MS Héb. 671.5 Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale. Leiden: Brill, 1994.

Bekkum, Wout Jac van, trans. A Hebrew Alexander Romance According to MS London, Jews’ College. Louvain: Peeters Press, 1992.

Darmesteter, Arsène, and D.S. Blondheim. Les Gloses Françaises Dans Les Commentaires Talmudiques de Raschi. Paris: Champion, 1929.

Donitz, Saskia. “Alexander the Great in Medieval Hebrew Traditions.” In A Companion to Alexander Literature in the Middle Ages, edited by Z. David Zuwiyya, 21–40. Leiden: Brill, 2011.

Fudeman, Kirsten Anne. Vernacular Voices: Language and Identity in Medieval French Jewish Communities. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011. See pp.101-102 for discussion of this couplet.

Kazis, Israel, ed. The Book of the Gests of Alexander of Macedon. Translated by Israel Kazis. Cambridge: Medieval Academy of America, 1962.

Reich, Rosalie. “Tales of Alexander the Macedonian.” Ph.D. Dissertation, New York University, 1967.

Yassif, Eli. “The Hebrew Traditions about Alexander the Great: Narrative Models and Their Meaning in the Middle Ages / המסורות העבריות על אלכסנדר מוקדון: תבניות סיפוריות ומשמעותן בתרבות היהודית של ימי הביניים.” Tarbiz 75, no. 3/4 (2006): 359–407.