Beyond the codex: some historico-political songs in Anglo-Norman England

Stefano Resconi is a postdoctoral researcher in Romance Philology and Linguistics at the Università degli Studi di Milano. His research is centred on the comparative study of Romance lyric traditions, French romances and the sources of Dante. Stefano is currently spending three months with the TVOF team as a visiting researcher.

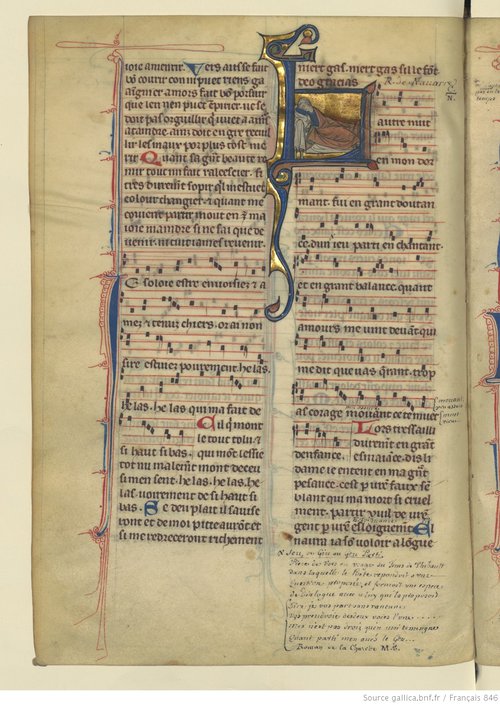

As with almost every medieval French literary genre, the codex is the typical physical support for transcribing and transmitting lyric poetry. The textual tradition of the trouvères is, alongside that of the troubadours, the most extensive in the domain of medieval Romance lyric, and the richest of all in terms of the presence of chansonniers provided with musical notation (see right). Since the ground-breaking study of the troubadour tradition by Gustav Gröber, we know that the extant Romance lyrical manuscripts collect and re-order texts (often according to an ideological purpose) from less substantial and structured material supports. Liederblätter (‘single sheets’) and rotuli (‘rolls’) are two of these kinds of mediums. The poets themselves talk about these objects, which are occasionally portrayed in the decoration that accompanies certain manuscripts of the texts.

Let us consider, for instance, the portrait of the troubadour Folquet de Marselha we find (see below left) on folio 63r of Provençal chansonnier N (New York, The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.819). It shows the poet nearly fainting, overwhelmed with an erotic despair that does not let him continue with the composition of the text he is writing on a roll. This is exactly the situation described in the opening lines of Folquet’s poem Meravill me cum pot nuills hom chantar (BEdT 155,13), written alongside the drawing in the manuscript:

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, fr. 846 (chansonnier français O), f. 69v. Source: gallica.fr

New York, The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.819, f. 63r (particular). Source: http://ica.themorgan.org/manuscript/page/24/147160

Meravill me cum pot nuills hom chantar

si cum ieu fatz per lieis que·m fai doler,

qu’e ma chansso non puosc apareillar

dos motz qu’al tertz no·m lais marritz chaser,

car non sui lai on estai sos cors gens,

doutz e plazens,

que m’auci desiran

e non pot far morir tant fin aman.

(vv. 1-8; critical text by Paolo Squillacioti)

(I’m amazed that any man could sing like I do for the lady who makes me suffer: I can’t put two words together in my song without, when I arrive at the third, letting myself fall, dazed, because I’m not where her gentle figure is, sweet and pleasant, that kills me through desire and can’t make such a perfect lover die.)

With a few exceptions, this kind of support had the principal function of fixing in writing and transmitting (potentially with a view to performance) texts as short as the lyrical ones are: thus, they did not usually need to be made of durable, refined and expensive material. Together with the small size that made them particularly fragile, this is probably the reason why only a few of them have survived.

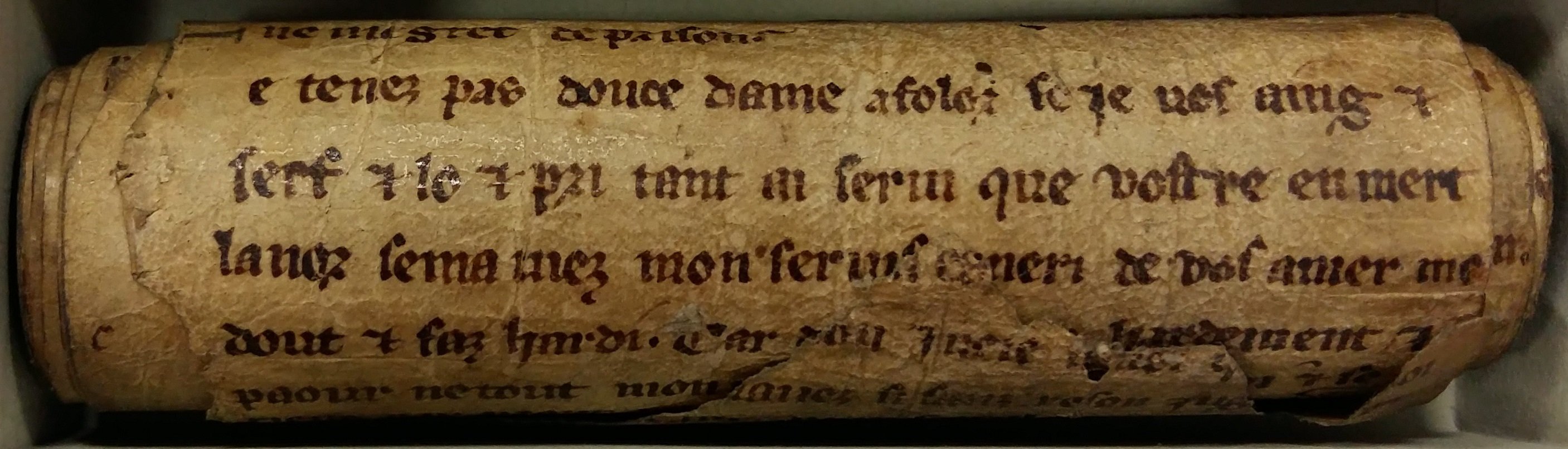

MS 1681 of Lambeth Palace Library in London is one of these lucky survivors (see below). It is a roll (about 1 metre long and 11.5cm in width, damaged at the top) written in England at the beginning of the fourteenth century, transmitting seven lyric poems that we can read also in the chansonniers (two chansons written by the Châtelain de Coucy and Gace Brulé – RS 1872 and 565 –, followed by a collection of Artesian jeux-partis). During the reign of Edward III (1327-1377) the verso was filled with Latin texts concerning English local history, suggesting that the roll was probably circulating in an administrative social context. The visual arrangement of the text within the roll points to interesting similarities with the fragments of another mid-thirteenth-century lyric roll, which contains poems of the Minnesänger Reinmar von Zweter. In this roll, the text is written in scriptio continua with metrical punctuation and coloured lettrines mark the first line of each stanza, while in the Lambeth Palace roll the letters were planned but not completed as there is blank space for the two-line-height initials at the beginning of each poem. This important artefact shows that a roll was perfect for transcribing short collections of lyrical texts that did not require the vast space of a codex, ensuring a practical and compact material support.

London, Lambeth Palace Library, MS 1681. Source: personal picture. Reproduced with permission from Lambeth Palace Library. Catalogue description here.

If the texts added on the verso side of Lambeth Palace roll may indicate its circulation in political-administrative contexts, it is interesting that lyric or para-lyric texts copied on supports different from the codex in medieval England often deal with historical or political topics. This is not only the case with the type of objects we having been looking at – sheets or rolls originally intended for transcribing lyric poems –, but also with so-called ‘traces’ (texts written in blank spaces within already complete codices). Indeed, the oldest surviving transcription of a Romance lyric poem is a French chanson de croisade (RS 1548a, Chevalier, mult estes guariz) added by an English hand from the second half of the twelfth century in the blank space following Gregory the Great’s Moralia in Iob in ms. Erfurt, Universitätsbibliothek, Dep. Erf. Codex Amplonianus 8° 32.

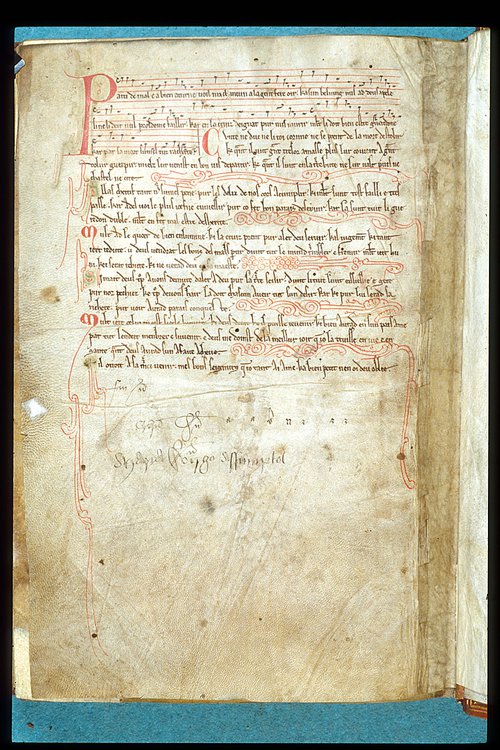

An historico-political text also characterises the oldest surviving Romance Liederblatt, embedded in a manuscript of Benoît de Sainte-Maure’s Cronique des ducs de Normandie (London, British Library, Harley MS 1717, fol. 251v) (see below right). On this sheet (originally the internal part of a single bifolium – this material feature shows some similarities with another important although later Romance lyric bifolium, the Pergaminho Vindel) we can read a text provided with musical notation, written at the end of 1180s by a member of Henry II’s court and transcribed in the same period and in the same context. The poem, Parti de mal et a bien atourné (RS 401), is again a chanson de croisade, and this is its only attestation. Its author hopes that the settlement of the conflicts between Henry II, his sons and Philip Augustus will finally give the Plantagenets the opportunity to focus their military energies on the crusade:

Si m’aït Deus, trop avons demuré

d’aler a Deu pur sa terre seisir

dunt li Turc l’unt eisseillié e geté

pur noz pechiez ke trop devons haïr.

La doit chascun aveir tut sun desir,

kar ki pur Lui lerad sa richeté

pur voir avrad paraïs conquesté.

(vv. 29-35; critical text by Anna Radaelli)

(God help me, we have delayed too long in going to God to seize the land from which the Turks have exiled and banished Him because of our sins, which we should profoundly hate. On this each one of us should concentrate his whole desire, since whoever leaves his riches for His sake will certainly have conquered paradise [translation by Anna Radaelli])

London, British Library, Harley MS 1717, f. 251v. Source: British Library Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts.

Finally, we may also consider the so-called Song of the Barons, transcribed on the recto side of a roll (London, British Library, Add. MS 23986, unfortunately now lost) dating to the end of the thirteenth century or the beginning of the fourteenth. The poem, probably written in 1263, refers to the Second Barons’ War, and its author sides with Simon de Montfort, who is highly honoured in the seventh stanza, where a flattering etymology is given for his name:

Il est apelé de Montfort: (He is called of Montfort

Il est el mond et si est fort, he is in the world and he is strong,

Si ad grant chevalerie; and great is his prowess;

Ce [est] voir et je m’acort: this is the truth and I concur:

Il eime dreit et het le tort, he loves right and hates wrong

Si avera la mestrie. and he will get the upper hand.)

(vv. 37-42; critical text and translation by Isabel S. T. Aspin)

If we consider the palaeographic features of all the objects that we have looked at, we notice that – despite the material support that may seem unusual to us – the texts are transcribed with the objective of giving them a dignified appearance: the transcriptions are made in a professional way, and are provided with ample paratextual decoration. This may suggest that this kind of Liederblätter and rotuli is not representative of the material supports made for immediate use by the poets, the performers of their texts, or their admirers. They were more likely special transcriptions designed to collect a small number of poems (sometimes even a single one) on relatively stable supports that could be offered as a gift to someone, circulate in a particular environment (probably a political one in the case of the last two artefacts we have considered), or simply to ensure a better preservation.

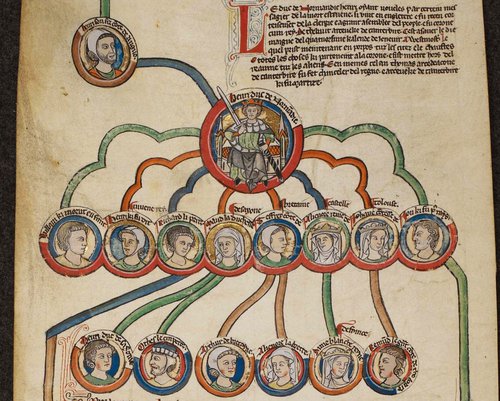

Moreover, medieval England provides us with other episodes that show the circulation of political-historical texts on material supports other than the codex. Indeed, the Anglo-Norman genealogies on rolls are one of the most widespread ways of reading history in medieval England from the end of the thirteenth century (see right). By combining texts belonging to the complex constellation of the Brut abrégé with remarkable artistic representations of genealogical trees, these artefacts aimed to give a complete but at the same time brief idea of English history, from the legendary arrival of Brutus (or, more often, from the Heptarchy) to contemporary times and beyond. Some of the rolls in fact show added skins containing later corrections or updates, attesting the constant interest of medieval readers for historical texts, even when written outside the codex.

London, British Library, Royal MS 14 B VI (genealogical roll; particular of Henry II and his descendants). Source: British Library Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts.

Bibliography:

Aspin, Isabel S. T., Anglo-Norman Political Songs, Oxford, Anglo-Norman Text Society, 1953.

Avalle, D’Arco Silvio, I manoscritti della letteratura in lingua d’oc. Nuova edizione a cura di Lino Leonardi, Torino, Einaudi, 1993.

Beltran, Vicenç, Tipología y génesis de los cancioneros: del Liederblatt al cancionero, in La lirica romanza del Medioevo. Storia, tradizioni, interpretazioni. Atti del VI Convegno triennale della Società Italiana di Filologia Romanza (Padova-Stra, 27 settembre – 1 ottobre 2006), a cura di Furio Brugnolo e Francesca Gambino, Padova, 2009, II, pp. 445-472.

De Laborderie, Olivier, Histoire, mémoire et pouvoir. Les généalogies en rouleau des rois d’Angleterre (1250-1422). Préface de Jacques Le Goff, Paris, Classiques Garnier, 2013.

Marcenaro, Simone, Nuove acquisizioni sul Pergaminho Vindel (New York, Pierpont Morgan Library ms. 979), in «Critica del Testo», XVIII/1 (2015), pp. 33-53.

Radaelli, Anna, ‘Voil ma chançun a la gent fere oïr’. An Anglo-Norman Crusade Appeal (London, BL Harley 1717, fol. 251v), in Literature of the Crusades. Edited by Simon T. Parsons, Linda M. Paterson, Cambridge, D.S. Brewer, 2018, pp. 109-133.

Resconi, Stefano, Tracce, ricontestualizzazioni, canali di trasmissione peculiari: percorsi tra le liriche oitaniche trascritte al di fuori dei canzonieri francesi, in «Critica del Testo», XVIII/3 (2015), pp. 169-198.

Tyson, Diana B., The Manuscript Tradition of Old French Prose Brut Rolls, in «Scriptorium», LV (2001), pp. 107–118.

Rouse, Richard H., Roll and Codex. The Transmission of the Works of Reinmar von Zweter, in Paläographie 1981. Colloquium des Comité International de Paléographie. München, 15.-18. September 1981. Referate. Herausgegeben von Gabriel Silagi, München, Arbeo-Gesellscheft, 1982, pp. 107-123.

Wallensköld, Axel, Le ms. Londres, Bibliothèque de Lambeth Palace, Misc. Rolls 1435, in «Mémoires de la Société Néo-Philologique de Helsingfors», VI (1917), pp. 3-40.