Feminine fury or motherly love? The Cimbrian women in the Histoire ancienne jusqu'à César

The Histoire ancienne provides a number of different accounts of women going to war, from the all-conquering Semiramis in Orient I, ‘qui ot cuer d’ome [et] samblance de feme’ (Fr20125 § 374, 2) (who had the heart of a man but looked like a woman), to the ultimate warrior women, the Amazons, whose origins are recounted in section 4 of our edition. Elsewhere, the individual feats of Camilla, who ‘forte estoit [et] hardie [et] chiualerouse plus que nulle autre creature’ (Fr20125 § 617, 12) (was strong, brave and more chivalrous than any living being), play a key role in Turnus’s opposition against Eneas. These exceptional women often become the subject of manuscript illuminations.

The Amazons arrive to assist the Trojan defence, from London, British Library, Add. 15268, f. 122r. Reproduced with the permission of the British Library Board.

The lengthy account of Roman history features a particularly harrowing example of women taking to the battlefield. In 101 BC, at the Battle of Vercellae, the Romans led by Gaius Marius put an end to the Cimbrian War (113-101 BC) with a crushing victory over three Germanic tribes, the Teutones, the Ambrones and the Cimbri. In the midst of battle, the Cimbrian women, rather than being enslaved by the Romans, construct a makeshift fort out of wagons and chariots, and fight valiantly against their opponents. When they begin to realise that they have little hope of victory, they perform a mass suicide, either by sword or noose, taking their children with them.

In the Histoire ancienne (Fr20125 § 1148, 1-3), we read:

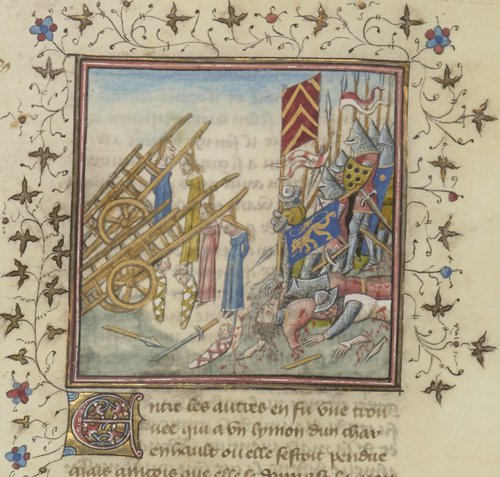

Tantost com cele bataille fu definee cest que li cimbrien furent trestuit mort [et] pris [et] uencut firent lor femes une grant merueille· quar eles assamblerent trestos les cars a [345ra] quatre roies [et] les charretes de lor ost entor eles si en firent forterece por eles guarandir· [et] si mo[n]terent sus les pluisors bien armees· [et] les pluisors tenoient fors espious aceres [et] haches esmolues· [et] dars [et] saietes [et] autres armes trenchans por eles defendre[/] Cestes par lor grans fiertes esmuirent uers les romains ausi aigre bataille por eles contretenir en lor forterece poi sen failli come lor segnor auoient faite·[et] mout longement firent les romains en sus deles traire par les ars [et] par les saietes do[n]t eles les agreuoient· [et] par les espious· [et] par les dars esmolus do[n]t eles les lansoient· mais puis q[ue] li romain refurent uergonde de ceste merueille؛ il lor corurent tant aigrement sore quil en ocistrent pluisors [et] couperent les testes as espees nues· De ce sesmaierent les femes mout durement en eles meismes [et] si en entrerent en tel desesperance de lor uies [et] en tel deruerie queles pristrent les armes esmolues q[ue] les tenoient si en tuerent lor enfans [et] en apres eles meismes· les pluisors apres ce queles orent totes mortes lor maisnees se couperent les goules· [et] les pluisors sestranglerent· [et] teles iot qui as pies des cheuaus loierent cordes [et] puis si les lacierent en lor cous [et] tantost laisserent les cheuaus al[er]· qui les estranglerent [et] trainere[n]t [b] [et] des pluisors drecierent contremont les trinons des chars si se pendirent la as cordes par les cous tant queles orent perdues les uies·

(As soon as this battle was over, when the Cimbrian men were all dead, captured or vanquished, their wives performed a great marvel, as they assembled the four-wheeled wagons and the chariots from their army and made a fortress around them for protection. Then many of them climbed on top of it with their weapons, wielding very sharp spear tips and keen axes, and darts, arrows and other piercing weapons with which to defend themselves. These women, out of their great pride, brought a bitter battle against the Romans to defend their fortress, just as the men had done. The Romans beneath them were much afflicted by the darts and arrows, as well as by the spear tips and keen missiles which were thrown by the women. But since the Romans were put once again to shame by this marvel, they most bitterly retaliated, killing many of them and chopping off their heads with just their swords. This troubled the women very much, and they lost all hope for their survival, and in a great frenzy, they took their sharpened weapons and killed their children before taking their own lives. Many others, after having put their households to death, slit their own throats, or strangled themselves, and there were even those who put ropes around their necks and attached these ropes to the hooves of horses, so that they would be dragged behind them and strangled. Many more positioned their wagons vertically so that they could hang themselves high up from the wagon pole and as such lost their lives.)

The Cimbrian women against the Romans, from London, British Library, Royal 20 D I, f. 337r. Reproduced with the permission of the British Library Board.

The source of this passage can be found in the late-antique Historiae adversum Paganos (Book 5, chapter 16) by Orosius. The same sequence of suicides—slitting their own throats, being dragged around by horses, and hanging themselves from their wagons—is presented in the Latin source. One of the main differences between the two versions is their explanation for why the Cimbrian women chose to kill themselves. According to Orosius,

sed cum ab his nouo caedis genere terrerentur - abscisis enim cum crine uerticibus inhonesto satis uulnere turpes relinquebantur - ferrum, quod in hostes sumpserant, in se suosque uerterunt.

([The Cimbrian women] finally became terrified by a new method employed by the Romans in killing enemies. The Romans scalped the women and left them in an unsightly condition from their shameful wounds.)

While it does mention the beheading of the women, the Histoire ancienne does not explicitly reference their scalping. Both suggest that the trauma of the battlefield was hugely affecting, but in Orosius there is specific reference to how the Romans brutally tore out their hair and the associated shame of being scalped.

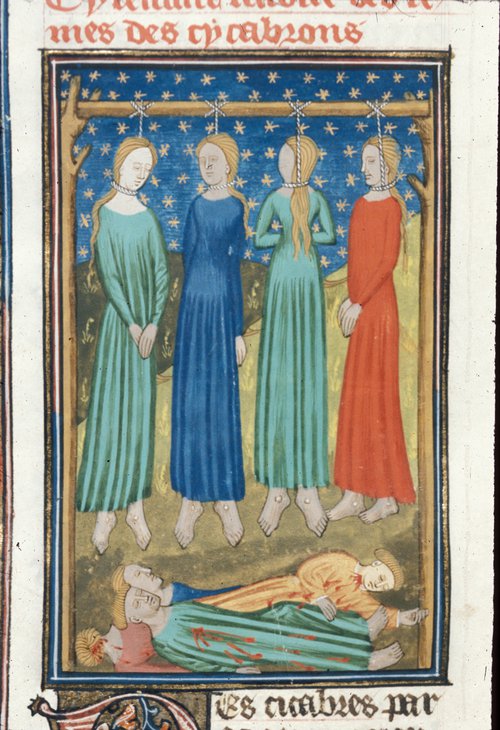

The suicide of the Cimbrian women, from Paris, BnF, f. fr. 250, f. 215r. Source: Gallica.BnF.fr.

One of the Cimbrian women is described by both Orosius and the compiler of the Histoire ancienne in particular detail. She commits suicide by hanging herself atop a wagon pole, along with her two children whose nooses are attached to her feet:

Entre les autres en fu trouee une qui a un timon dun char en haut o ele estoit montee sestoit pendue mais ansois quele sabandonast a la mort ne quele sesbouionast ius dou car puis quele se fu par le col enlacee loia ele a ses ·ii· pies ·ii· siens enfans par les cous si come feme enragee (Fr20125 § 1149, 1)

(Among the women one was found who had climbed atop a wagon and hung herself from the pole. But before abandoning herself to death, it was not just her that perished from atop the wagon, since, as a woman filled with rage, she had put nooses around the necks of her two children and hung them from her feet.)

The addition of 'si come feme enragee' ('as a woman filled with rage') departs slightly from Orosius. The compiler of the Histoire ancienne attempts to explain the extreme acts of the mother, driven by intense desperation and indignation. By contrast in Orosius, the description of 'feminine fury' (femineo furore) appears as a general comment on the Cimbrian women's behaviour at the end of the episode in the Latin text, in which he also underlines how they acted 'with manly strength' (ui uirili).

The representations of the Cimbrian women by both Orosius and the compiler of the Histoire ancienne stress their pride and fortitude, yet also refer to the exceptionality of the event (it is a 'marvel', merueille). They attest an ambiguous treatment of female behaviour, and in particular motherhood. On the one hand, the women are accused of exhibiting an excess of feminine fury, emboldened by remarkable physical strength. On the other, the implication remains that the Cimbrian women act in order to save their children from the dishonour of servitude, where it is actually their maternal devotion that partly explains the harrowing events.

The depiction of the Cimbrian women is rare in the corpus of Histoire ancienne manuscripts. One of the few examples is found in one of the earliest copies from northern France: London, British Library, Additional 19669. In a four-compartment miniature, the women are shown at battle in their carts in the bottom left, and in the bottom right, their suicide is depicted, including the woman who hung her children from her feet.

The manuscripts which share the same cycle of illuminations as Additional 19669 do not include this final scene. The four-compartment miniature in The Hague (f. 179rb) features the Cimbrian women fighting and their suicide, but omits the death of the children.

London, British Library, Add. 19669, f. 218v. Reproduced with the permission of the British Library Board.

By contrast, the late fourteenth-century copy found in Paris, BnF, f. fr. 250 (see above), includes a miniature which focuses on the suicide of the women following the bloody battle, and makes an explicit reference to the act of infanticide described in detail.

London, British Library, Royal 16 G V, f. 94v. Source: British Library, Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts.

In this period, we find the slightly more positive portrayal of the Cimbrians in Giovanni Boccaccio's De claris mulieribus ('On famous women', written c.1362), in which the author attempts partly to rationalise the infanticide and juxtaposes the honourable women with the greedy, plundering Romans.

Bocaccio writes,

Quod cum honestissimum visum foret et sincere mentis testimonium, nec impetrassent, succense furore in obstinatam voti sui perseverantiam per sevum ivere facinus. Nam ante omnia, collisis in terram parvis filiis atque peremptis, ut illos, qua poterant via, turpi servitati subtraherent, nocte eadem intra vallum a se confectum, ne et ipse in dedecus sue castitatis et victorum ludibrium traherentur, laqueis omnes lorisque mortem conscivere sibi nec prede aliud ex se preter pendentia cadavera, avidis liquere militibus.

(Burning with rage, the women then committed a terrible deed in their inflexible determination to keep their vow. First they killed their little children by dashing them against the ground — the only possible way to save their offspring from a life of degrading servitude. That same night, in the confines of the stockade they had built, the women hanged themselves with ropes and bridle reins so as to avoid dishonour to their virtue and the mockery of their conquerors. Dangling bodies were the only plunder left for the greedy soldiers.)

Here Boccaccio also concentrates on the 'frenzy'/'rage' (furore) of the women that leads them to act and avoid the dishonour of becoming slaves (turpi servitati). Boccaccio in the subsequent passage goes onto explain that the women, rather than attempting to plead with the Romans by using their sexual appeal ('soluto crine, tensis manibus', their hair loosened, their hands raised), therefore retain their 'feminine dignity' (honestatis feminae).

The case of the Cimbrian women must have fascinated, scandalised, and horrified medieval audiences, emphasised in the absence or the sheer viscerality of the illuminations. The significant number of surviving manuscripts of later translations of Boccaccio, notably in French, Martin le Franc's Le Champion des Dames, as well as the Histoire ancienne jusqu'à César show that ancient history, especially when narrating the extremes of human behaviour, was a rich source of information for questions about gender and identity in the late Middle Ages.

Hannah Morcos & Henry Ravenhall

Texts and Translations cited

—Giovannio Boccaccio, De claris mulieribus (La Biblioteca Italiana), accessed 22 May 2018.

—Giovanni Boccaccio, trans. Virginia Brown, On Famous Women (Cambridge: Harvard

University Press, 2003).

—Orosius, Historiae adversum Paganos (The Latin Library), accessed 22 May 2018.

—Orosius, A History against the Pagans (Christian Historical Documents), accessed 22 May 2018.

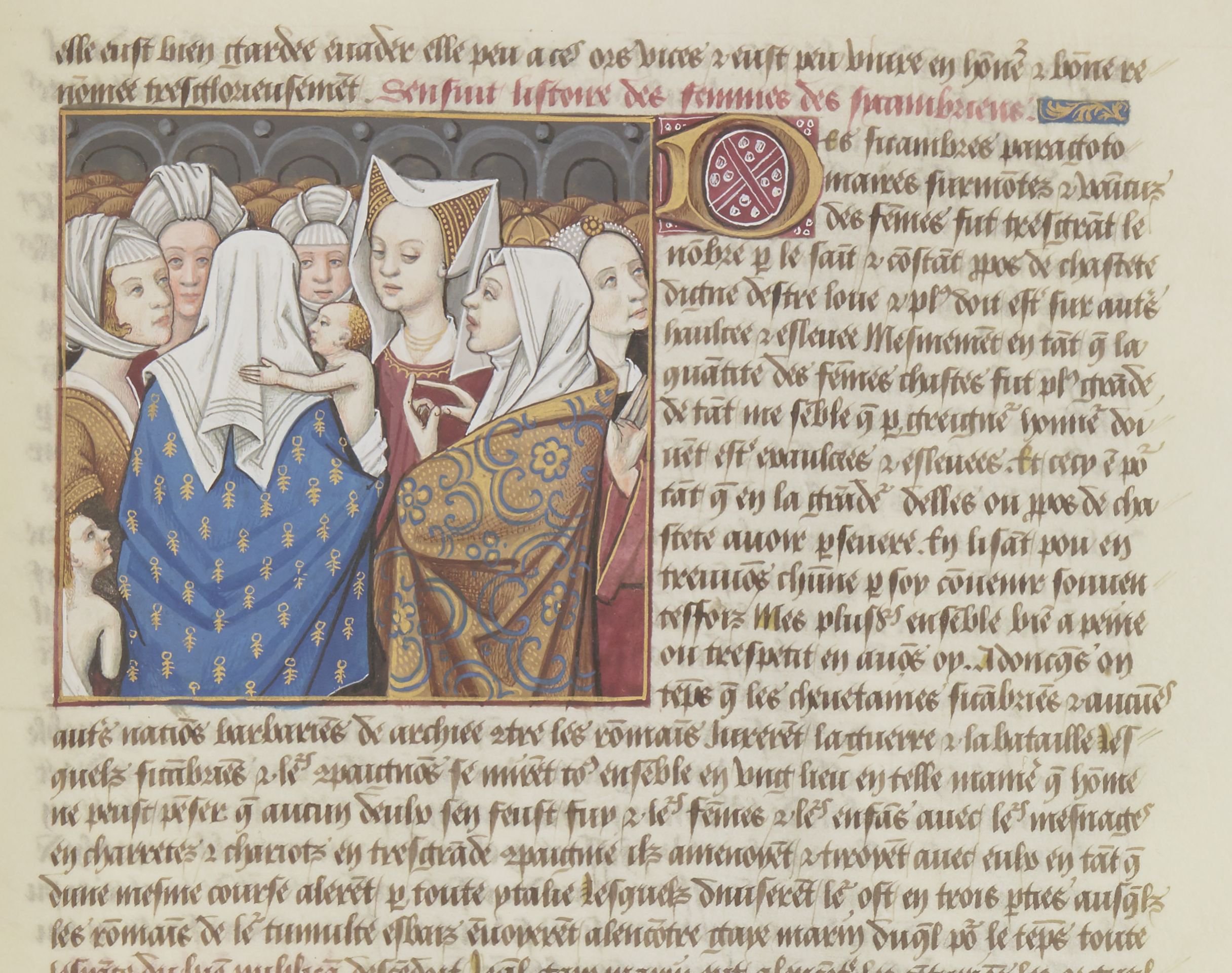

Laurent de Premierfait, Des cleres et nobles femmes, from Paris, BnF, f. fr. 599, f. 69r. Source: Gallica.BnF.fr.