Preaching in Verse in the Contes moralisés

Sarah Bridge is a DPhil candidate in Medieval and Modern Languages at St Hilda’s College, University of Oxford. Her research looks at the audience and reception of the works of Nicole Bozon, an Anglo-Norman author of the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries.

Although his work has been largely neglected by modern scholarship, the Franciscan friar Nicole Bozon was arguably one of medieval England’s most prolific and popular authors. Active at the turn of the fourteenth century, he authored around thirty works, which are transmitted by an impressive number of manuscripts. Like a great deal of Anglo-Norman literature, these texts are generally religious and didactic in nature, but range in form from saints’ lives, to passion poems, to collections of proverbs.

Amongst these is the Contes moralisés, written around 1320, which stands out as both Bozon’s only prose work, and his only work to use English and Latin alongside French. Like much of his oeuvre, the Contes moralisés has clear moralising aims, made apparent by its opening line:

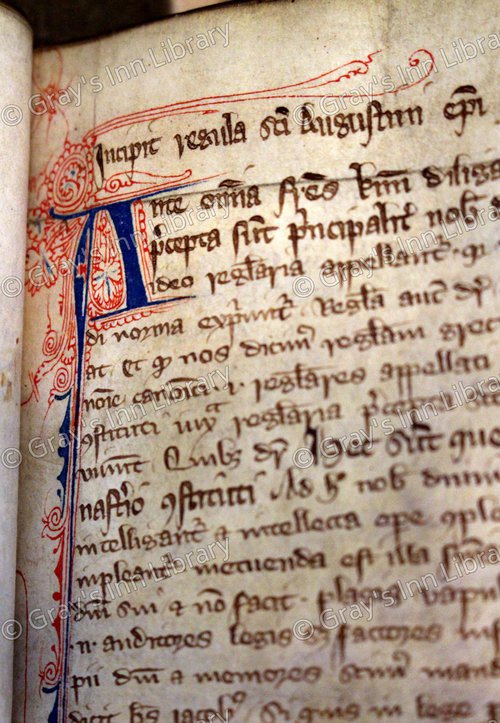

The beginning of one of the Latin sermons from Gray's Inn, MS 12 , f. 51ra. See online images here. Reproduced with kind permission from Gray's Inn Library.

‘en ceo petit livret poet l’em trover meynt beal ensaumple de diverse matiere par ont l’em poet aprendre de eschuer peché, de embracer bontee, e sur tote rien de loer Dampnedee’

(Les Contes moralisés, Ch. 1; eds. Toulmin-Smith and Meyer)

‘In this little booklet, one can find many fitting examples from diverse materials, by which one can learn to avoid sin, embrace goodness, and above all else to praise God’

(All translations are my own)

Fittingly, the transmission context of the Contes moralisés suggests that it was used for preaching. It is found in two manuscripts; the first of these, British Library, Additional MS 46919 lists the text in a ‘table of contents’ on its first folio as ‘exempla bona et narrationes utiles per sermonibus’ (good examples and useful stories for sermons). This manuscript belonged to, and was compiled by, William Herebert, lector to the Franciscans at Oxford in the mid-fourteenth century, and also contains a number of Latin sermons, along with the date and location of their delivery. The second manuscript which preserves the text, Gray’s Inn, MS 12, also points to use of the Contes moralisés in preaching; its co-texts here are a number of Latin sermons and a preaching manual.

In form and content, then, the text is a typical exempla collection; a collection of short, moralising stories for use in preaching, the like of which saw enormous popularity amongst the Franciscans in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. However, the use of French for the main body of the text is highly unusual. In fact, the Contes moralisés is the only extant example of the genre from this period in England not to be written in Latin. Although it is likely that a great deal of preaching was done in the vernacular, as is suggested by contemporary preaching manuals, we have a limited picture of what this might have looked like. The majority of extant sermon material is written in Latin, leading us to assume that those who wished to use it to preach in the vernacular would have had to improvise or translate ex tempore. The Contes moralisés is also far more detailed than other exempla collections. Where similar Latin texts often provide only outlines of narratives, and do not always spell out their moral applications, the Contes moralisés is made up of complete stories, with their relation to human behaviour explicitly stated.

The Contes moralisés, therefore, provides us with a rare example of what vernacular preaching using exempla might have looked like in the fourteenth century. It is interesting to note that the language of the text is highly crafted and deploys a range of rhetorical techniques to persuade and engage the audience. Perhaps the most striking of these are the moments of verse which pepper the prose of the text. Take, for example, chapter 42:

Par mesme cest ensample peot l'em dire coment le low e le herison devendrent compaingnons tant qe le lou prist un agneile e f̈ui sui des chiens et des bastons, e prist son congee del hericeoun d'eschaper au bois. « Ha! » dist le herison, « baisez moy a congé prendre. » — « Volenteres, fet le lou, et au beisere le hericeon lui erda al menton. L'autre escowe la teste e ceo veut deliverer, mes ceo ne fust pur rien: od lui maugree le seon lui porta. Le lou est pechour, le hericeon od les espinez si est péché qe ferme se lye al pecheour; sicom dit Salomon: Iniquitas eius cum ipso est.

(Les Contes moralisés, Ch. 42; eds. Toulmin-Smith and Meyer)

To give a similar example, one can tell the story of how the wolf and the hedgehog became friends, when the wolf seized a lamb and fled, followed by dogs and sticks, and took his leave of the hedgehog to escape to the woods. “Ha!” said the hedgehog “kiss me for helping you escape”. “Gladly” said the wolf, but when he kissed him, the hedgehog stuck to his chin. The wolf shook his head and tried to free himself, but he couldn’t do it at all: he carried the hedgehog with him in spite of himself. The wolf is the sinner, the hedgehog with its spines is the sin which firmly attaches to the sinner: just as Solomon says: his iniquity is with him.

An image of a hedgehog from f. 97v of British Library, Royal MS 2 B VII. See the BL catalogue for more details. Reproduced with permission from the British Library Board.

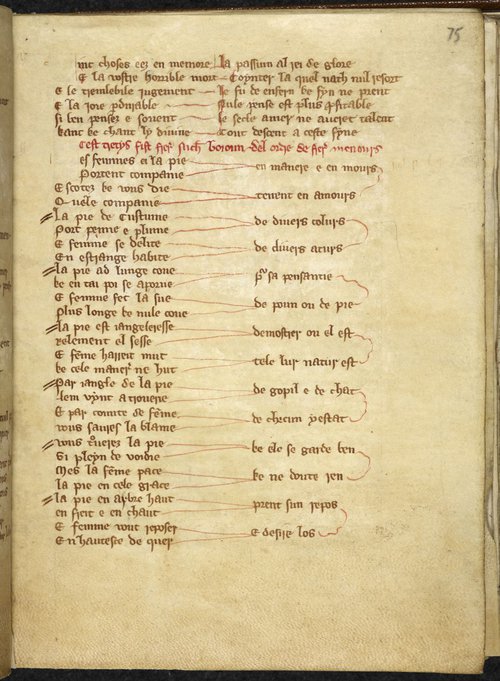

A verse text attributed to Bozon, British Library, Additional 46919, f. 75r. See the BL catalogue for more details. Reproduced with permission from the British Library Board.

Highlighted here in bold are two rhyming phrases, typical of those which appear throughout the text. The first is (almost) an octosyllabic couplet, with eight syllables in the first line and nine in the second – a perfectly permissible metre by Anglo-Norman standards. In the second example we have another octosyllabic line, and then the preservation of the rhyme word ‘menton’ to rhyme with ‘hericeon’.

Previous scholars working on the Contes moralisés have attempted to identify these verse interludes with possible sources for the text, with limited success; it is equally possible that they are of Bozon’s own creation, as he authored at least ten further texts, all of which are in verse. Either way, the frequency and placement of these poetic moments suggests that that Bozon made a deliberate choice to either retain or create verse within his exempla.

What, then, is the purpose of this poetic prose, and what can it tell us about vernacular preaching? The answer may lie in what Gerald Owst, in his seminal 1966 work, called ‘the literature of the pulpit’. Poetic form enabled preachers to make their material pleasurable and memorable, and therefore convey their spiritual message effectively. Alan J. Fletcher goes so far to argue that we should not see poetry and preaching as separate entities, but rather appreciate that the sermon was “both a host for, and a generator of” vernacular poetry (Fletcher, p. 275). The Contes moralisés, as an example of a vernacular preaching text, demonstrates how this worked in practice. This text is therefore an important reminder of the value of literary creativity in religious communication (something which cannot always be recovered from its Latin equivalents), and of the reciprocal and co-operative relationship between preaching and vernacular poetry.

Sarah Bridge

References:

Alan J. Fletcher, Late Medieval Popular Preaching in Britain and Ireland: Texts, Studies, and Interpretations (Turnhout: Brepols, 2009).

Gerald R. Owst, Literature and Pulpit in Medieval England: A Neglected Chapter in the History of English Letters & of the English People (Oxford: Blackwell, 1966).

Lucy Toulmin-Smith and Paul Meyer (eds.), Les Contes moralisés de Nicole Bozon, Frère Mineur (Paris: Firmin Didot, 1889).