The Shape of Vernacular History

Alexander Peña received his B.A. in History and English from Williams College, and is currently a doctoral candidate in the Medieval Studies program at Yale University. His research interests center broadly on Mediterranean inter-religious cultural and intellectual history, memory studies, translation studies, literary theory, and medieval historiography and chronography. He focuses particularly on these themes in the Iberian peninsula and with respect to Christian, Muslim, and Jewish relations in the high Middle Ages. His dissertation will examine the translation of Arabic historiographical texts and other sources of Islamic as well as Jewish thought into Latin and the vernacular in Western Europe in the 12th and 13th centuries.

Among the papers presented at the Narrating History Across Languages conference, the theme which stood out most to me was that of disorientation. However, it was disorientation put to good use, deployed to encourage new ways of thinking about medieval histories, chronicles, and other historical texts written in vernacular languages like French and German (as opposed to elite registers like Latin), primarily between the 12th and 15th centuries. To this end, our conference participants explored when, why, and how medieval historians used the vernacular in their writings to navigate contested spaces, elaborate on old themes, and comment on contemporary issues. The papers also emphasized cross-European and Mediterranean literary and cultural networks, treating traditionally “peripheral” areas (such as Spain, southern France, the Near East, Sicily, and Crimea) as centers of change and innovation in their own right.

Robert Bartlett delivered a brilliant public lecture at the British Library entitled ‘The Languages of History in the Middle Ages’.

Disorientation also served as a subject of inquiry and study in and of itself. From Simon Gaunt’s opening exploration of the tension which characterized the innovative use of French as a language for writing within the genre of universal chronicles; to Rosa María Rodríguez Porto’s closing narration of the emergence of illustrated vernacular histories, not in traditional “centers” of manuscript production like Paris, but in multilingual and multicultural environments like Spain and the Middle East: the conference traced the disoriented, diverse, often ad hoc, and always multifaceted developments and practices of vernacular history-writing in a variety of historical, geographic, and cultural contexts.

It’s worth noting that special attention was paid to postcolonial approaches to medieval texts. The papers demonstrated an acute awareness of the social conditions and structures of power within which vernacularity was employed. We thus saw how the use of the vernacular had the potential to: confront established traditions of history writing (Simon Gaunt, Mark Chinca); function in the service of social and cultural resistance (Jill Ross); bridge and mediate various linguistic and cultural traditions (Serena Ferente, Rosa María Rodríguez Porto, Julian Weiss); and facilitate emotional and affective engagement between the authors and the historical events they wrote about (Karla Mallette).

![Alphonse_X_de_Castille_Cronica_[...]Alfonso_X_btv1b8436387q.jpg](/media/images/Alphonse_X_de_Castille_Cronica_...Alfonso_X_bt.width-500.jpg)

Paris, BnF Espagnol 12, f. 188r. MS dated to 1440-60, copied in Naples. Source: Gallica.bnf.fr

My own current research as a doctoral candidate focuses on translation and the writing of history in the Middle Ages. When, how, and why did medieval history-writers seek, translate, and incorporate foreign-language histories, chronicles, and other texts into their own compositions (both in Latin and in the vernacular)? Focusing on Iberia in particular, I’m also exploring how history-writing and translation projects functioned as tools of conquest, accompanying more familiar tools such as warfare and forced religious conversion as a means of assimilating, altering, and erasing foreign historical narratives and identities. The conference participants each offered invaluable insight for critically examining medieval negotiations of language and for understanding how medieval historians engaged with, and shaped, their own pasts as well as the pasts of others.

Simon Gaunt’s utilization of literary theory in his discussion of the French Histoire ancienne jusqu'à César (of which two particularly beautifully illuminated manuscripts are currently being curated and exhibited at the British Library, courtesy of graduate students at King’s College London – read about this here) offered insights into the self-conscious use of the vernacular in history-writing. Gaunt demonstrated how the French-writing author of the Histoire ancienne (a universal chronicle of the ancient past) self-consciously and self-referentially juxtaposed his narration with more traditional languages of “universal history” such as Latin and Hebrew. At stake in the use of French to write universal history was not just a matter of readership; it was a matter of ownership of the past, and of who could narrate it.

Julian Weiss’s description of cultural translation had particular relevance for my own studies, as his work touched on issues of appropriation, assimilation, and cultural communities. Reading the 14th-century Mocedades de Rodrigo (see left), a Castilian poem about the youthful exploits of the legendary Spanish hero, El Cid, Weiss explored the text’s mediation of Spain’s relationship to the rest of Europe. Weiss interpreted the poem as a narrative which simultaneously denied Spain’s “peripheral” status vis-à-vis the continent, while also appealing to and appropriating European norms of hegemony. Because my own work deals with the ways in which medieval historians responded and adapted to culturally and linguistically foreign narratives, Weiss’s discussion of medieval re-drawings of cultural and historical boundaries was particularly useful for thinking about how translation could itself serve as a tool for negotiating boundaries and re-imagining shared pasts.

Jill Ross’s inspired paper utilized postcolonial theory to elaborate how the vernacular could be used both as a way of reconciling different literary traditions as well as a form of cultural resistance. Her reading of the Majorcan author Guillem de Torroella’s Arthurian tale, La Faula, situates the text firmly within political and cultural struggles of the late 14th century. Amidst heightened tension and aggression between the disputed crown of Majorca and the king of Aragon on the mainland, La Faula deployed French – a language privileged in the Aragonese court – and an Arthurian frame for its allegory of contemporary political events, despite a historical Majorcan ambivalence regarding French cultural hegemony and Arthurian literature itself. I found most compelling her navigation of Torroella’s appropriation and destabilization of hegemonic tools of power, specifically the French language and courtly French literature. In pointing out these subversive techniques for historical and literary narration, Ross explored a “poetics of loss” within the narrative of La Faula, contributing to a massive and still-growing discussion around the intersection between literature and the writing of history in the Middle Ages.

Cover to Anna Maria Compagna's 2004 edition of La Faula published by Carocci. Available here.

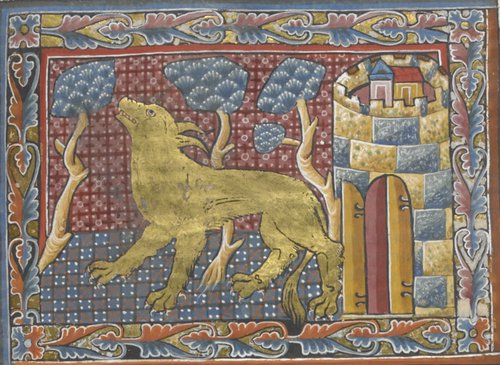

British Library, Additional 15268, f. 95r. Digitisation available here. Reproduced with permission from the British Library Board.

Returning to the theme of trans-Mediterranean networks, Rosa María Rodríguez Porto’s presentation (download here) powerfully considered how new models for representing history through images emerged in the Middle Ages in response to, and alongside, the development of vernacular historiography itself. Her talk traced the emergence of elaborately illustrated vernacular chronicles in culturally pluralistic (and, perhaps notably, crusading) societies such as those of the Iberian peninsula and the Levant, demonstrating how the confluence of various cultures and linguistic traditions played a key role in the elaboration of these illustrated histories. If vernacularity stimulated new ways of thinking visually about the past, as in two of the manuscripts discussed by Rodríguez Porto, the Spanish Estoria de España (Seville, 1270) and the French Histoire ancienne (Acre, late 13th century), then we can also think about other ways in which vernacularity simultaneously shaped, and was shaped by, other developments in intellectual and cultural history.

As an Iberianist myself, most of my responses here have been to the (much welcomed) proportion of scholars who presented on Iberian topics. All of the papers, however, were a pleasure to hear and interact with, and I wish I had space to discuss all of them in detail. Nonetheless, the amount of contact which could be, and was, held between Iberianists and scholars of French, Italian, German, and Eastern European historiographies and literatures, was a heartening and critically engaging testament to both the achievements of the conference and to the importance for more spaces and opportunities like it.