Evolving texts and evolving witnesses

We have already shown on several occasions how the Histoire ancienne’s textual tradition contains some outstanding examples of variation, and how this complex body of disparate knowledge was adapted to suit new tastes, didactical needs and cultural contexts. Sometimes single manuscripts offer evidence of such mutability not only when compared with other witnesses, but also through their own internal structure. The material act of structural modification left important traces, which we can still observe and analyse today.

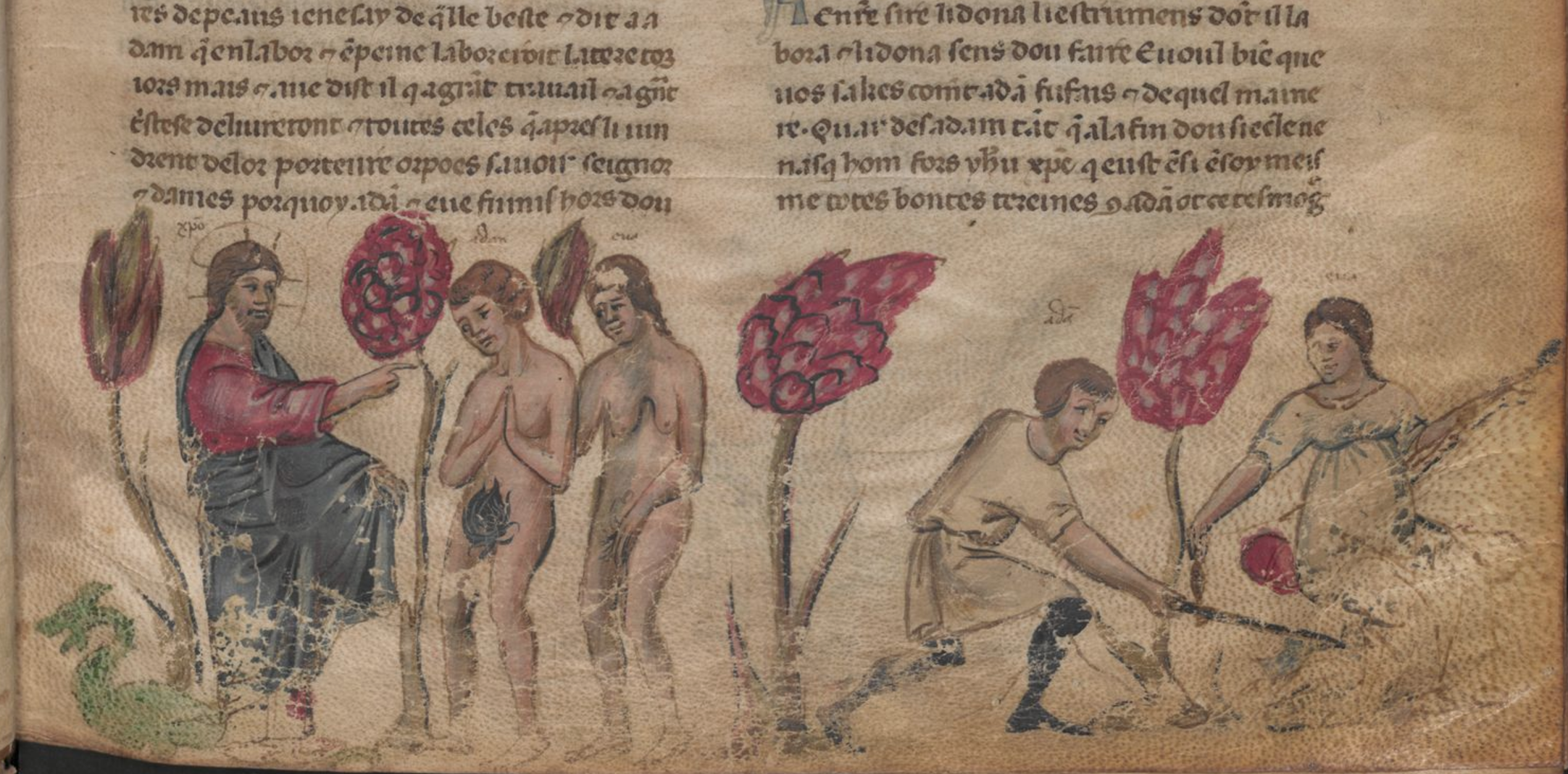

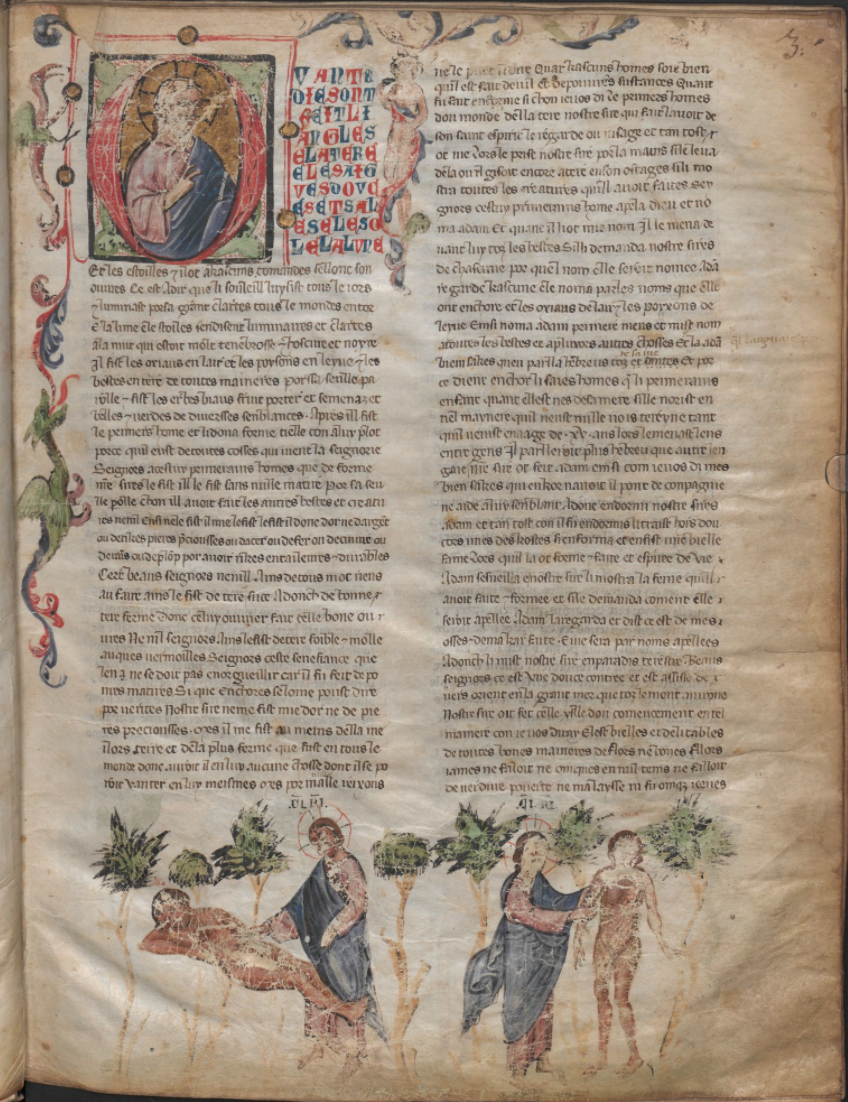

Vienna, ÖNB, Cod. 2576, f. 4r: Adam and Eve exiled from paradise. Reproduced with the permission of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (source: www.onb.ac.at).

Two Histoire ancienne manuscripts illustrate this phenomenon particularly well. In recent years, research on Paris, BnF, fr. 17177 and Vienna, ÖNB, 2576 has shown how modifications made to texts and manuscripts can offer insights into the less predictable aspects of manuscript circulation, for example unique interpolations and the inclusion within the same witness of material from different parts of the textual tradition

MS fr.17177 of the Bibliothèque nationale de France is a late 13th-century codex, copied in France, which features a unique and heavily abridged version of the Histoire ancienne. This manuscript was produced, as Gabriele Giannini has shown, in an atelier in the diocese of Soissons. Interpolated into the Histoire ancienne here is the oldest extant French prose translation of Geoffroy of Monmouth’s Historia regum Britanniae, based directly on the Latin text with some localised borrowings from Wace. Géraldine Veysseyre’s linguistic analysis in her critical edition suggests the translator was Picard.

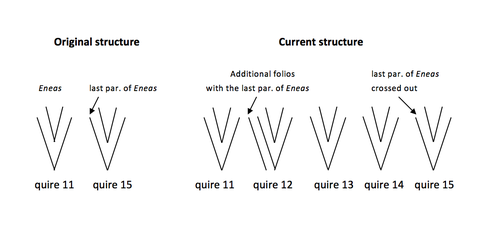

Original and current structures of BNF fr. 17177

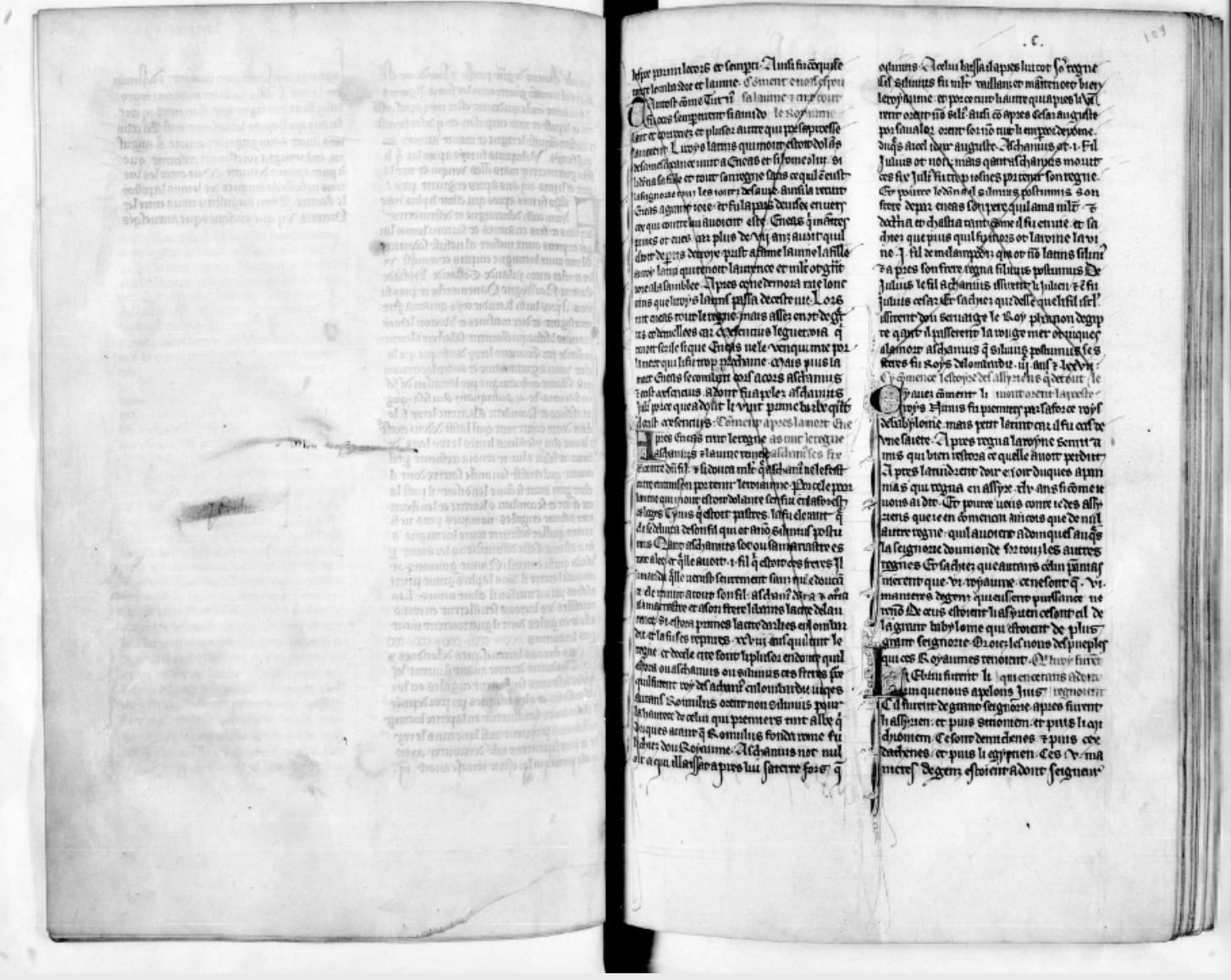

This prose Estoire de Brutus is inserted in the Histoire ancienne just after the Eneas section. But the insertion was implemented at a late stage in the manuscript’s production, after the Histoire ancienne had already been copied. In order to insert the Brutus in the desired position, the last paragraphs of the Eneas section, which opened a new quire, were crossed out and copied again on a new folio, which is then inserted before the Brutus.

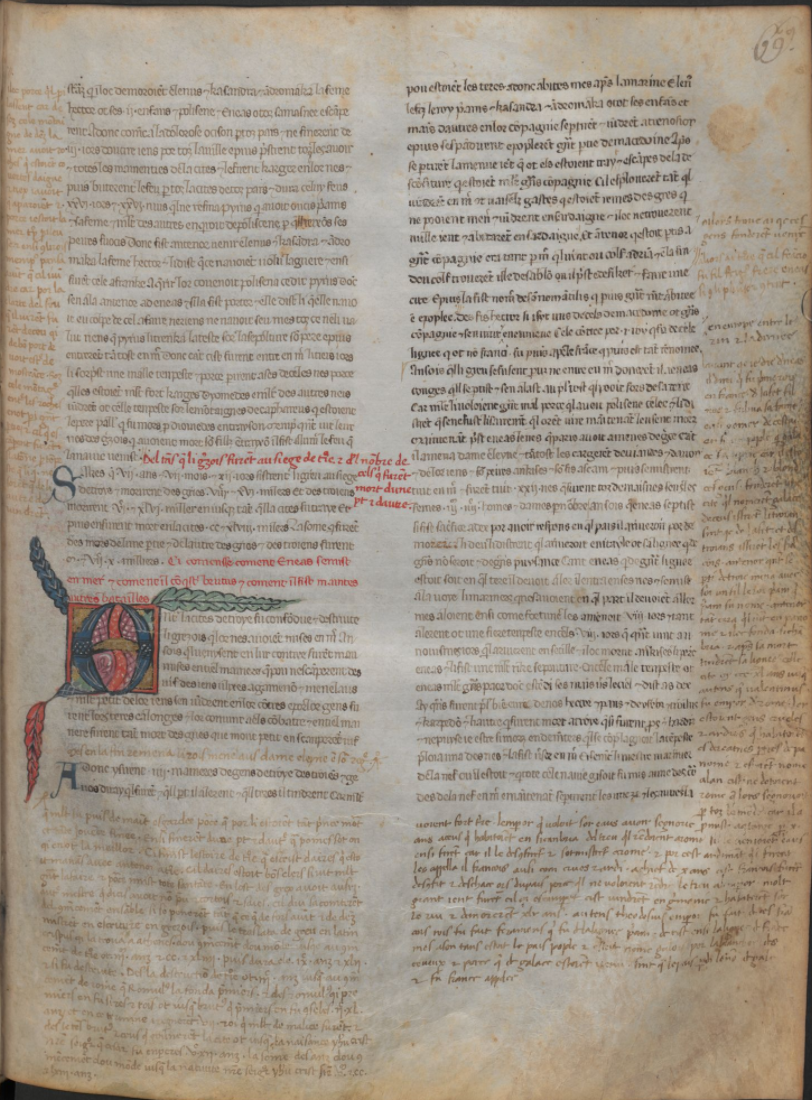

Paris, BNF fr. 17177, ff. 108v-109r: the crossed paragraphs at the beginning of quire 15. Reproduced with the permission of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (source: www.gallica.bnf.fr).

The structure of the manuscript was significantly modified, leaving indelible scars. Yet this somewhat clumsy act led to the preservation of a unique witness to the continental reception of the Historia Regum Britanniae, an otherwise unattested tour de force of translation from a highly rhetorical Latin text, which avoided oblivion only because of its last-minute integration into a copy of the Histoire ancienne.

If Bnf fr. 17177 was apparently modified in the atelier responsible for its production, the case of Vienna, ÖNB, cod. 2576 is even more interesting: this unique codex is the outcome of the work of different scribes, operating over a long period of time to produce a copy of the Histoire ancienne that used different and diverse models.

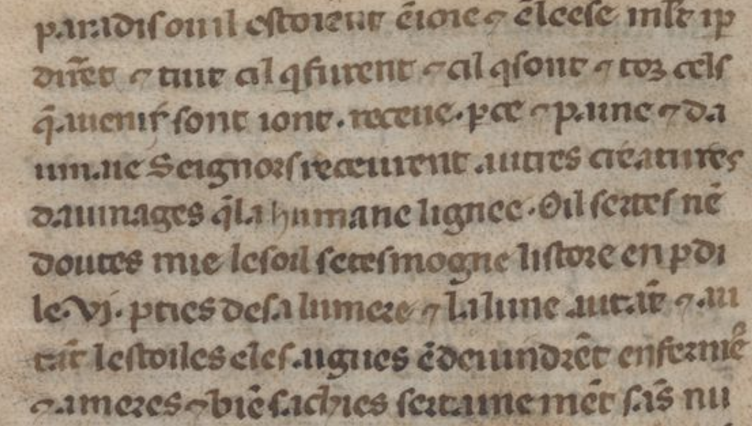

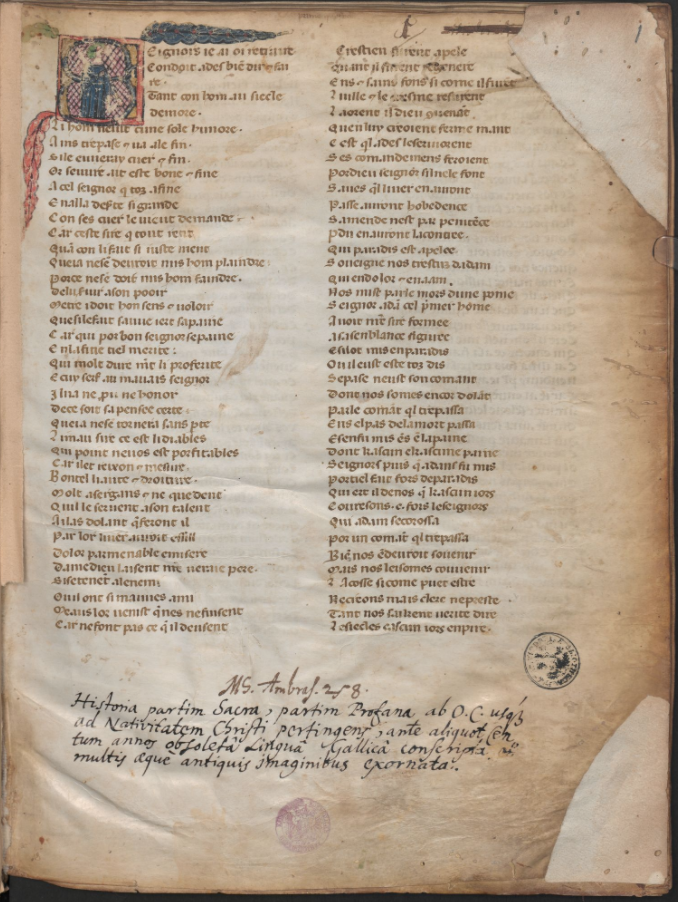

This manuscript is one of the most interesting witnesses of the Histoire ancienne, because it is the only one, together with BnF fr. 20125, to transmit the verse prologue. This implies that this 14th-century manuscript, copied in Venice, drew on a very good (and presumably old) source. However, as Matteo Cambi recently pointed out, the manuscript is the product of the activity of at least three scribes: the first two, A and B, operated in the first half of 14th century; the third, C, was active at the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries.

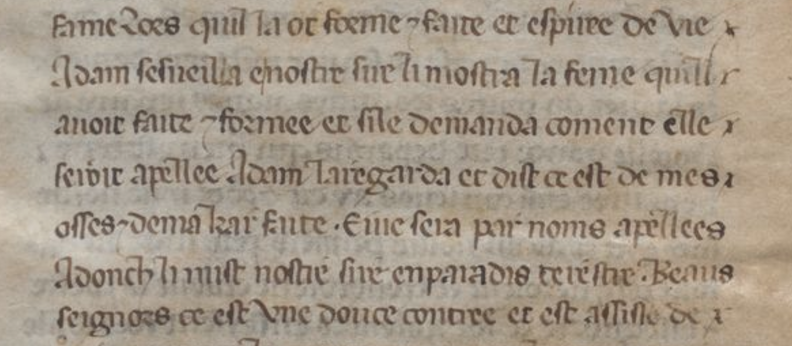

Vienna, ÖNB, Cod. 2576, f. 4r: scribe A. Reproduced with the permission of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (source: www.onb.ac.at).

Vienna, ÖNB, Cod. 2576, f. 3r: scribe B. Reproduced with the permission of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (source: www.onb.ac.at).

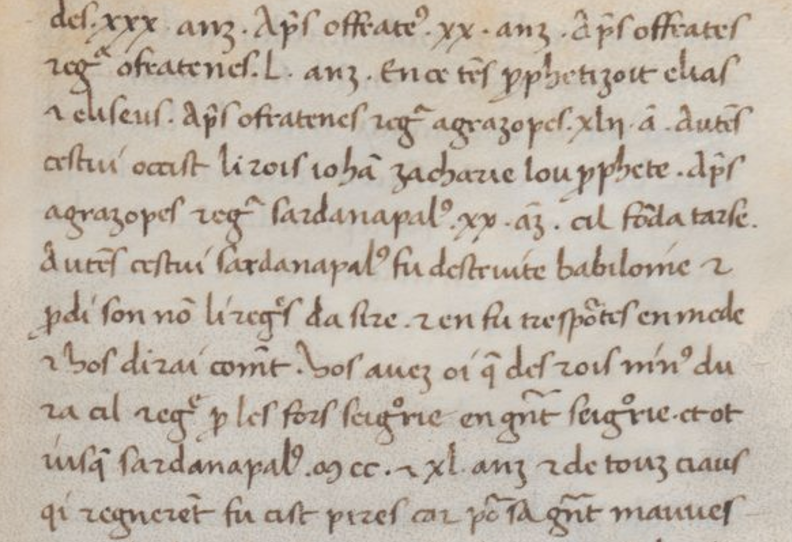

Vienna, ÖNB, Cod. 2576, f. 73r: scribe c. Reproduced with the permission of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (source: www.onb.ac.at).

Unusually the work of the three scribes is not sequential, but rather interlaced. Scribe B seems to have continued and modified the work of scribe A, then scribe C revised and modified the work of his predecessor even more heavily, adding rubrics and substantial additional material in the margin as well as correcting portions of the text.

Vienna, ÖNB, Cod. 2576, f. 1r: verse prologue copied by scribe A. Reproduced with the permission of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (source: www.onb.ac.at).

Vienna, ÖNB, Cod. 2576, f. 3r: beginning of Genesis copied by scribe B. Reproduced with the permission of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (source: www.onb.ac.at).

Vienna, ÖNB, Cod. 2576, f. 169r: scribe C adds rubrics and additional text to a page copied by scribe B. Reproduced with the permission of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (source: www.onb.ac.at).

The sources used by the three scribes were very different, as different as their approaches to exploiting them. While the details of this multiple copying enterprise have yet to be clarified, we already know that the source of the prologue is just one of those on which the compilers of the Vienna manuscript drew over a period of more 30 years or more (the time span which separates scribe C from scribes A and B). In addition, they used more recent versions of the Histoire ancienne, as well as otherwise unattested rewritings, to complete and modify the original source, giving the 15th-century Venetian readers of this book a unique experience of textual modification in a book which they could see with their own eyes was the result of textual stratification and layered production.

Vienna, ÖNB, Cod. 2576, f. 9v: the tower of Babel. Reproduced with the permission of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (source: www.onb.ac.at).

The material signs of textual change that we find in BnF fr. 17177 and Vienna, ÖNB, 2576 are exceptional in the vast textual tradition of the Histoire ancienne, since most manuscripts conceal any innovations they contain behind the façade of a clean copy. But exceptions such as these offer precious evidence of cultural mobility and of the complex reality of how the textual tradition evolved. Readers of these books were made perfectly aware of how the Histoire ancienne came to them in an innovative and unique form, made up from multiple sources of knowledge, from different times and places.

Bibliography

M. Cambi, ‘Note sull’Histoire ancienne jusq’à César in area padano-veneta (con nuove osservazioni sul ms. Wien, ÖNB, 2576)’, in Forme letterarie del Medioevo romanzo: testo, interpretazione e storia. XI Congresso della Società Italiana di Filologia Romanza, ed. by Antonio Pioletti and Stefano Rapisarda, Soveria Mannelli 2016, pp. 145-161.

G. Giannini, ‘L’Arsenal 3114 et la production de manuscrits en langue vernaculaire dans l’ancien diocèse de Soissons (1260-1330) environ’, in Les centres de production des manuscrits vernaculaires au Moyen Âge, ed. by G. Giannini and F. Gingras, Paris 2015, pp. 89-135.

G. Veysseyre, L’Estoire de Brutus. La plus ancienne traduction en prose française de l’Historia regum Britanniae de Geoffroy de Monmouth, Paris 2014.