Ovid as historian in 13th- and 14th-century Europe (work in progress)

In this guest blog post, Irene Salvo García discusses her research project on the historiographical use of Ovid's texts in medieval Europe, and how the Histoire ancienne jusqu'à César could be an important piece of the puzzle. Irene is a Marie Curie postdoctoral fellow at the Centre for Medieval Literature (Odense) and is currently a visiting researcher as part of the TVOF team.

Ovid († AD 17), the poet of mythology, the poet of love, is extraordinarily present in texts dealing with universal history in the Middle Ages. His works, especially those about mythology such as the Metamorphoses and the Heroides, are used as authorised sources to talk about the Pagans in the ancient history of Greece and Rome. Alongside Abraham and Moses, Alexander and Nebuchadnezzar, one meets Saturn, Jupiter and their heirs. The historiographical usage of Ovid, or Ovidius historicus, though innovative and surprising, can be related to prior manifestations. Canonical authors for history and ancient wisdom, such as Isidore of Seville (†636) or the Venerable Bede (†735) quote the Latin poet. One of the first and most frequent references are verses 86-89 of Book I of the Metamorphoses (cf. Etymologies XI, De homine et portentis and the commentary on Genesis 1.26), where Ovid describes the creation of human beings, who, as opposed to animals, watch the sky and the stars:

‘Pronaque cum spectant animalia caetera terram / os homini sublime dedit, caelumque videre / iussit, et erectos ad sidera tollere vultus’

[On earth the brute creation bends its gaze, / but man was given a lofty countenance and was commanded to behold the skies; / and with an upright face may view the stars].

Ovid comparing the universe to an egg, as found in a 15th-century Belgian manuscript copy of the Metamorphoses. Source: Wikimedia commons.

With these references, Isidore and Bede integrate Ovid into the Biblical account of Genesis. This is the beginning of a link between the Latin poet and the narrative of the creation of the world, which will be a decisive element in his medieval reception. Besides, the most significant facts recounted by mythology have been included in Christian universal histories since Late Antiquity. Eusebius of Caesarea (†339) and Jerome (†420) mention the Flood of Deucalion and the myth of Phaethon, the war and the fall of Troy, or the love of Phaedra and Hippolytus in their incidentia, which appear as short passages inserted into their Chronological Canons. Medieval historians, inheriting these models and an encyclopaedic inclination to exhaustiveness, rely on the authors who added extra detail to the facts more so than on earlier sources (the ones that provided the overarching structure). Eventually, the glosses, the medieval commentaries that come with the works and auctores of the literary canon—the Bible in the first place, but also Ovid, Virgil and Orosius—end up shaping up the Metamorphoses and the Heroides into ‘exploitable’ works, both morally and historically. As a consequence, mythology is a part of the first Romance-language universal histories we know, such as the Histoire ancienne jusqu’à César (1st redaction, ca. 1208-1213 & 2nd redaction, ca. 1338), in Old French, or the General estoria (ca. 1270-1284) by Alfonso X, in Castilian, where Ovid’s texts take up a good 20% of the text—more than 1200 out of the total 6000 pages in its modern edition. In turn, the first autonomous translations of the Metamorphoses inherit the poet's historical interpretation: indeed, the underlying chronological structure of Ovid’s text, which starts with the creation of the world and finishes with Caesar Augustus, is naturally inserted into a wider chronological frame of ancient history. This feature is striking in the Ovide moralisé (ca. 1320), the first complete translation of the Metamorphoses in any Romance language.

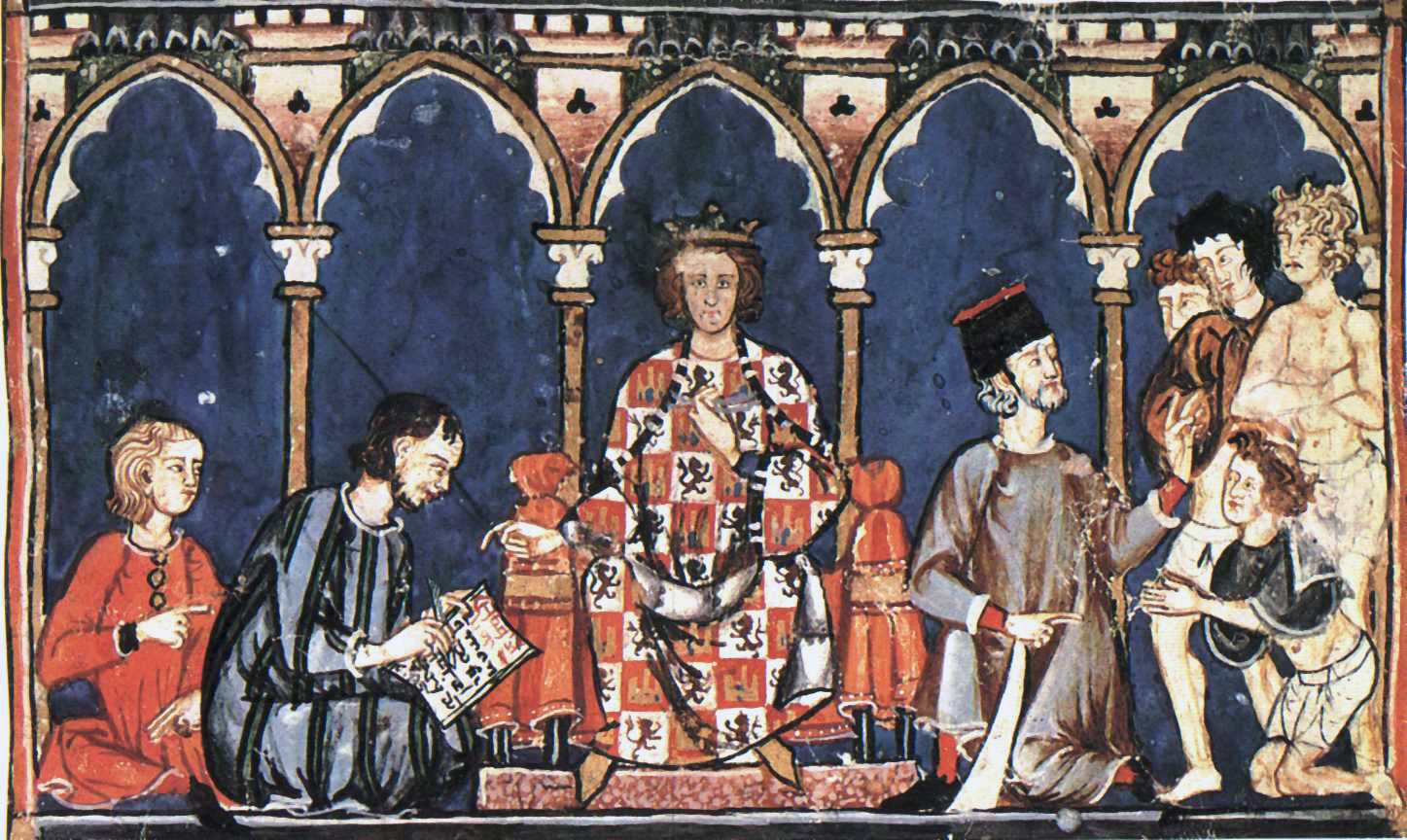

Alfonso X of Castile from the Libro de los Juegos. Source: Wikimedia commons.

In spite of the aforementioned works, the assimilation of Ovid and mythology into the historiography of the Middle Ages has not yet received, I think, the attention it deserves. Critics have mainly focused on the moralizing (or even ‘Christianizing’) character of Ovid's texts. However, it is astonishing how literal and tolerant readers and translators of Ovid were, and this would be worth studying. Literal, because the text, being considered as history, is treated as a (reliable/authoritative) document, and hence is not modified semantically. Tolerant as well, because, while the supernatural elements of the myth, the physical transformation, are interpreted as allegories or historical facts (euhemerism), the core of the story is directly translated. The relative bibliographical void may be due to an incomplete knowledge of the quoted works. This is understandable: the first complete edition of the General estoria was published only in 2009, and at present there are only partial editions of the Histoire ancienne. Thanks to the scholars who have progressively edited the latter in both of its versions, and to the team of the ongoing project The Values of French (TVOF), this gap will be promptly filled, and, as is happening with the General estoria, the scope and the impact of the Histoire ancienne will finally emerge, not only in French literature, but also across Europe more generally.

In my current project Romaine, Ovid as Historian. The reception of classical mythology in medieval France and Spain, I try to understand better the characteristics of, and the mechanisms that produced, the translations of Ovid dedicated to history in the Middle Ages. Since certain features of this translation in Spain can be observed in France a few decades later (over the late 13th and early 14th centuries), a comparative approach seems appropriate. The point is that the General estoria, the second-redaction Histoire ancienne and the Ovide moralisé not only share Ovid’s translation, but also a significant part of the corpus of source texts. Moreover, it was established long ago that the first redaction of the Histoire ancienne was known to Alfonso’s scriptorium, and that it was used as a partial source for the Matters of Troy and Thebes. These common features suggest that the authors and the contexts of composition were influenced by very similar intellectual dynamics. We are yet to identify these currents, and to establish how the works travelled across the Pyrenees.

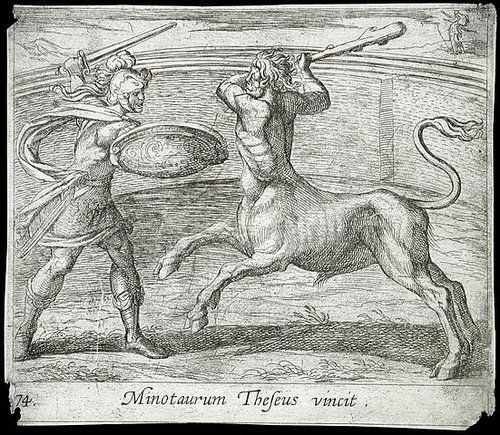

'Theseus defeats the Minotaur'. Etching in a copy of the Metamorphoses (1606). Source: Wikimedia commons.

These thoughts are a work in progress. Thanks to a three-month research visit at King’s College London, I have been able to talk to the members of TVOF and read new materials on the TVOF website. My assumptions have now been strengthened and refined. For instance, the new transcription of Aeneas’ episode (part VI) in the manuscripts Fr. 20125 (Histoire ancienne first redaction) and Royal 20 D.I. (Histoire ancienne second redaction) has led me to (provisional) conclusions.

This fragment contains an aparté about Pasiphaë and the story of the Minotaur, which was recently analysed by Hannah Morcos in this blog. In Alfonso’s General estoria (II, 1, p. 559-610), the same story includes very similar contents: not only the Minotaur's birth, but also its abduction and placement into Daedalus’ labyrinth, Theseus’ arrival and his victorious fight, his flight with Ariadne, who, with some thread, had helped him escape. Despite these common elements, one quickly notices differences in the treatment of the same episode, recounted by Ovid in the Metamorphoses (VII, v. 404 to VIII, v. 277) and by late-antique and medieval mythographers.

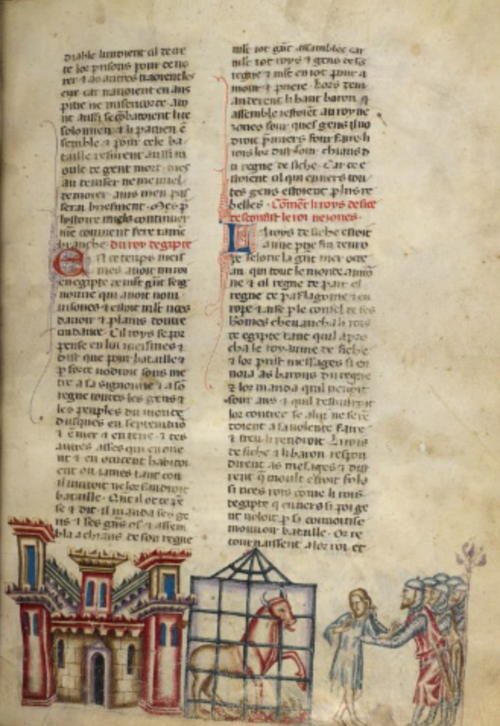

The first of these narrative episodes shows us that the General estoria and the Histoire ancienne may have common sources, but they follow different structural models. In the General estoria, the Minotaur episode is situated in the appropriate chronology, during Minos’ reign over Crete, following the Chronological Canons. The Minotaur is briefly mentioned in the manuscripts Fr. 20125 (§496) and Royal 20 D.I. (§44), at the same place as the General estoria, but the actual story, as found in the General estoria, is told alongside Aeneas’ arrival in the city of Cumae (Fr. 20125, §608, 8-21) or Italy (Royal 20 D.I., §536, 14-31). These chronological differences show that the General estoria takes the Chronological Canons and the Metamorphoses as models, while the Histoire ancienne follows Virgil’s Aeneid, glossed by Servius, as Hannah Morcos has duly noted. However, mythographic commentaries can move between texts. A gloss by Servius (Aen. 6, 14 in Fr. 20125, §609) claims that the bull (taurus) was a secretary (notaire) of Minos, and that the Minotaur is a reference to Pasiphaë’s twins born from simultaneous affairs with Minos and Taurus, the secretary. This gloss is received in Ovid’s commentaries such as the ones by Jean de Garlande (Integumenta Ovidii, ca. 1200, v. 321-323) and Giovanni del Virgilio (Allegoriae librorum Ovidii Metamorphoseos, ca. 1322, VIII, 2). A final characteristic emerges from this preliminary analysis: that there were criteria for how interpretations of mythological texts were to be selected. As Hannah Morcos remarks, Servius’ euhemeristic gloss about the Minotaur disappears from some manuscripts of the second-redaction Histoire ancienne such as Royal 20 D.I. (cf. §537), probably because the fictional nature of the tale does not prevent it from being treated as history. We observe a similar process in the General estoria and the Ovide moralisé (cf. VII, v. 2243 to VIII, v. 1708), where the rationalising gloss about the Minotaur and Pasiphaë’s encounter with the bull are not inserted into any of the two texts, while it is everywhere in the mythographic tradition from which they borrow their commentaries (e.g. Vatican Mythographers).

BL MS Royal 20 D I, f. 22r. Reproduced with permission from the British Library Board.

What do these latter omissions tell us? Is the gloss simply absent from the source the Castilian and the author of the Ovide moralisé used? In a forthcoming article (Les 'Métamorphoses' et l’histoire ancienne), I set up the hypothesis that the source for this episode belongs to a specific mythographic tradition, where the Minotaur is not explained rationally. Can we go as far as to assume that the same model influenced the new version of the narrative included in Royal 20 D.I., a manuscript where mythography, and especially Ovid, occupies a significant portion of the narrative? Now that we can work with complete texts, we will perhaps be able to answer this kind of question about Ovid, and more generally about the role of mythography in the writing of history in the Middle Ages.

Bibliography

Alfonso el Sabio, General Estoria, VI partes, Pedro Sánchez-Prieto Borja (coord.), 10 vol., Madrid, Biblioteca Castro, 2009.

Gracia Alonso, Paloma, “Hacia el modelo de la General estoria. París, la translatio imperii et studii y la Histoire ancienne jusqu'à César”, Zeitschrift für romanische Philologie vol. 122, 2006, p. 17-27.

Ovide moralisé, Poème du commencement du quatorzième siècle publié d’après tous les manuscrits connus, t. III, livres VII-IX, Cornelis De Boer, Martina G. De Boer et Jeannette Th. M. Van’t Sant (ed.), Amsterdam, Noord-Hollandsche Uitgevers-Maatschappij, 1931.

Ovid's Metamorphoses (translation) at http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/collections.

Salvo García, Irene, “Les Métamorphoses et l’histoire ancienne en France et en Espagne (XIIIe-XIVe s.) : l’exemple des légendes crétoises (Mét. VII-VIII)”, in ‘Ovidius explanatus’: Traduire et commenter les Métamorphoses au Moyen Âge, Paris, Classiques Garnier (forthcoming).